Sports

How I maintained financial discipline – Jay-Jay Okocha

But behind the dribbles and dazzling skills lies a man who had to navigate fame, money, pressure, and the reality of life after football.

In an exclusive episode of The Long Form, recorded during the SportsBiz Africa Forum in Kigali, Rwanda, Okocha explained how he managed to stay financially disciplined during his career and how those habits helped him long after he retired.

Okocha’s revelations about how he managed and continues to manage his finances come at a time when the debate over the so-called “entitled mentality” of former athletes is dominating public discussion.

In recent months, Nigerians have been confronted with painful reminders of the economic situation of many ex-footballers once their playing days are over.

The passing of legendary goalkeeper Peter Rufai in July reopened old wounds, with his family reportedly struggling to even cover burial costs.

Former defender Taribo West, visibly angry at Rufai’s funeral, declared that he would never allow his own son to play for Nigeria, citing how the country ‘abandons’ its heroes once they are no longer active.

Politicians such as Peter Obi also joined the conversation, lamenting how those who once brought pride to the nation are left to suffer.

Rufai’s family later denied claims of receiving large sums from the government, stressing that official support was minimal.

The debate underlined what many already knew: too many of Nigeria’s former stars are living in hardship.

No pension

“I think that’s the biggest challenge that athletes face because a lot of us don’t realise that it’s a short career. We don’t get pension. You are your own government. I was lucky to realise that,” he said.

He recalled the moment it dawned on him that money could disappear quickly.

“It hit me when I first bought my commercial property in Nigeria and in England. So you buy a property that you think you’ve paid huge money (for), but the income it generates in a month, that’s not much.

So, I now realised that for me to be going home every month with $10,000, I needed to invest millions. I needed to stay focused and invest. I realised early enough in my 20s. I was 23-24.”

Unlike many players who fall into the trap of chasing every business idea, Okocha said he kept his focus. “I said to myself, there is no need for me to be greedy and be involved in businesses I don’t understand because people bring all sorts to you, and I know that a lot of players got ripped off. I survived that because I wasn’t greedy. I can see my property.

Even if I’m unlucky and the property burns down, I still have your land to start a new life. The only business I was doing was property. I started deriving joy in knowing that these are my properties. So I kept on buying until I stopped playing.”

He explained that he always used separate income for different purposes. “My contract money is for investment. There is match bonuses. It’s enough for you to live and for you to buy toys if you want. It’s all about putting a structure in place, and if you are not winning enough matches, then you backpedal. It’s not every month that you go shopping. It’s not every year you buy a car.”

Setting boundaries

“They are part of your structure, they are part of your budget. And also make it clear to them that they have limited time. You are trying to set them up, and they have to make it count,” he said.

That honesty sometimes meant having hard conversations. “I’m the actor, I know what I’m going through. I know that I have a limited time. I know that if I fail, I won’t have the opportunity to give them a better life. I won’t have the possibility of setting them up. I make it clear that they can’t fail because I didn’t fail.

It’s not everybody that utilises it well. At least 80 per cent are okay, and they take some of the burden away from you when you retire.”

He went further, stressing the importance of protecting the immediate family he had built. “What sets you apart is your ability to make decisions. Even if you are investing in charity organisations, there’s always a limit. It’s in my interest to protect my own family that I’ve created because I don’t want them to go through what I went through, and I waste it because others fail to be independent.

So I will try my best to give you the best opportunity that I can to make it in life, which I think I did to an extent. But you should be able to say this is where the boundary is, because automatically you give them the foundation that you don’t have, you give them the startup capital that you never had and if they are serious, they can’t fail.

“If they fail, it’s none of my business. I can’t suffer because you decide not to be responsible. I’ve suffered, and I can’t keep suffering. I used to tell them. You have to be honest.

I bought houses for them, I was paying school fees for their children, so why can’t you just manage the business I’ve started for you in order to feed your family? I made sure they can never be homeless.”

His upbringing, he believes, gave him a strong sense of direction. “My upbringing, I had a good foundation in the sense that the area where I grew up, my tribe was business inclined. Most Igbos do business. I had a clear picture of what I wanted, and for me, it was all about making as much as I can to secure my future and my family’s future.”

Freelancer

I wasn’t bothered about the clauses. As time goes on, I realised that it’s getting a bit serious. As a young African player, you get calls from agents. What I used to do was give an agent that brings a good deal the mandate, but it’s never exclusive.

Throughout my career, I was like a freelancer, and I think that might have helped or hindered me because sometimes football can be about who you are dealing with.”

Above all, he knew that football would not last forever. That was why, when he saw his first big cheque, he saved it. “Of course, I saved. The nature of our job, we don’t get pension. You’re basically your government. From the day you stop playing, that’s it.”

He repeated what became his golden rule: “My contract money is for investment. Match bonuses is enough for you to spend. You have endorsements; it’s enough for you to buy toys. So those nice cars and watches.”

Dare to be different

At a time when so many of Nigeria’s former football heroes are struggling and even respected voices like Taribo West are warning young players to stay away from the national team, Okocha’s example stands out.

The former Super Eagles captain has practically shown that while systems and administrators may fail, careful choices, honesty, and discipline can make all the difference.(Premium Times)

-

News51 minutes ago

News51 minutes agoTinubu’s ambassador-designates in limbo

-

Business50 minutes ago

Business50 minutes agoCBN raises alarm over Nigeria fintech’s foreign reliance

-

Politics49 minutes ago

Politics49 minutes agoWe’ve no plans to impeach dep gov — Kano Assembly

-

Opinion1 hour ago

Opinion1 hour agoLeft behind but not forgotten

-

Politics1 hour ago

Politics1 hour agoWe Don’t Need Gov’s Support To Deliver Rivers For Tinubu – Wike

-

Politics47 minutes ago

Politics47 minutes agoElectoral Act: Amendment yet to be concluded – Akpabio tells critics

-

News45 minutes ago

News45 minutes agoKaduna Residents Protest Displacement Of 18 Villages By Bandits, Closure Of 13 Basic Schools

-

News43 minutes ago

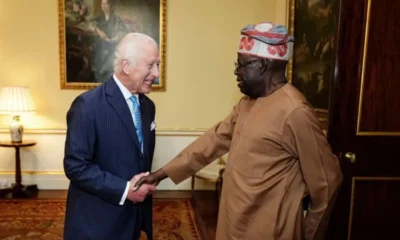

News43 minutes agoTinubu Set For First UK State Visit In 37 Years