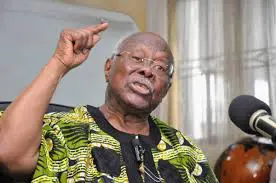

Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) leader Julius Malema has rarely been far from scandal. Since his rise in the 1990s through the militant ranks of the Congress of South African Students, allied to the African National Congress (ANC), he has faced persistent allegations of corruption, tax evasion, and abuse of office. Yet two decades later, Malema remains a dominant force in South Africa’s opposition politics.

In a new book, Malema – Money. Power. Patronage, Micah Reddy and Pauli van Wyk map out a trail of deals, trusts, and political manoeuvres that have raised tough questions about Malema’s finances and methods. The book quotes Malema as saying: “Donations from politicians and/or businesspersons have been part of my upbringing.”

Taunting the taxman

One of Malema’s earliest and most damaging battles was with the South African Revenue Service (SARS). At 23, he earned his first official paycheck of R12,500 ($723) as ANC Youth League provincial secretary in 2004. The ANC’s lax handling of employee tax meant Malema unknowingly defaulted; yet as his income grew from donations and business dealings, he still failed to comply.

Central to the saga was the Ratanang Family Trust, established in 2007 and named after his firstborn son. Malema never registered it for tax purposes despite attempts by SARS to help him achieve compliance. This eventually led to the attachment of some of his properties in order to pay the debt.

Undeclared property baron

According to the book, Malema has built a property empire over the years, currently comprising “at least nine” properties with an “understated” estimated acquisition value of R21.64m. He built a Sandton “bachelor’s pad” in 2011, a year before his expulsion from the ANC Youth League to start the EFF. The property, complete with an underground panic room and a party deck, was valued at about R16m but was later auctioned off by SARS to settle his tax debt.

Another more recent property acquisition is Mekete Lodge, which belonged to a close friend and which Malema acquired in 2020, five years after the friend’s death. Late night parties have taken place at the venue, including during the Covid-19 lockdown, even as Malema publicly supported the rules.

More recent upgrades to the lodge include “elaborate chandeliers”, marble cladding accented with inlaid brass on the walls and floors, replica elephants at the entrance, and emerald velvet recliners with USB ports in the armrests in the bar. Staff told the authors that the trimmings were imported from Dubai. It’s unclear who funded these renovations even though such funds would need disclosure. There’s also his R4m luxury flat in Hyde Park, Johannesburg — located near a house owned by cigarette smuggler Adriano Mazzotti, where Malema’s family once stayed.

He’s been a member of parliament since 2014 but has consistently only declared modest assets, not property, in spite of the full disclosure required by law. Some of his properties are bonded, but it’s not clear who pays the installments, the book states. This would amount to a violation of ethics rules, even perjury. He would not have been able to afford all of this on his parliamentary salary, currently at R1.27m per year before tax.

Undeclared trust assets

Malema has complied with rules by declaring family trusts like Ratanang and Munzhedzi, but millions of rands have passed through these trusts, while the assets, which include property, haven’t been declared.

According to the authors, Malema has violated all the core rules that define a trust. “There was no separation between his assets and those of the trust,” they say in the book. For example, the “bachelor’s pad” was funded with money that flowed through the trust, yet the property remained in Malema’s name. He also bought designer clothes, property, food and alcohol with trust funds.

VBS Mutual Bank heist

Malema and senior EFF figures, including his former deputy president Floyd Shivambu who has since defected, have been linked to the looting by a number of politicians of VBS Mutual Bank.

The scandal devastated poor, rural community members who had invested their little savings in the bank. ANC leaders have also been implicated in the looting, and serious prosecutions for the scandal, which broke in 2018, are yet to begin.

Abusing power for personal enrichment

The authors argue that Malema has consistently used political power to build his wealth, which has been growing exponentially since he became COSAS president in 1997. Despite damning evidence, he has never been prosecuted for corruption, possibly due to the political position he holds. He frequently casts himself as a victim when faced with action from institutions like SARS over his taxes.

The book also questions whether Malema – who has been EFF leader for over a decade now – would be able to keep growing his wealth if he didn’t have political power. They liken him to former president Jacob Zuma, flourishing “in the not-quite-legal and sometimes outright illicit economy where politics and business blended seamlessly”.

The book describes instances where Malema used his political influence in the Limpopo province, or municipalities, to have tenders awarded to friends and allies – who in turn reward him with “donations”, some of which is used for the party, and some for himself.

Undeclared party funding

The EFF has declared very few sources of funding, as required by the Political Party Funding Act, claiming they have been encouraging a number of donors to donate amounts below the R100,000 threshold required for disclosure. The book outlines how patronage networks ensure funds flowing to the EFF via tenders, trusts, and businesses connected to Malema’s associates.

This flow of funds isn’t always transparent, and often it’s quite deliberately covered up. For example, former party insiders told the writers how Malema would appear with the cigarette smuggler, Mazzotti, in public. It would raise eyebrows within the party, but they’d look the other way.

“The EFF was desperate for funds, and if Malema’s backers in the business world were willing to chip in, so be it,” they said. Malema told party members that, for the party to get to where it wanted to be, “we are going to have to kiss a lot of frogs on the way”.

Lavish rallies with spectacular special effects, and well-resourced election campaigns suggest that the party is receiving donations that it’s not declaring. Authorities have no teeth to enforce funding declarations, and no capacity to double-check on these either.

Alleged abuse of party funds

Some EFF leaders have expressed resentment over having to fund party activities from their own pockets. MPs are expected to pay 15% of their salaries to the party as a kind of tithe, and cover their own party organising costs, among others. Councillors in impoverished areas are expected to pay for buses to get party supporters to rallies – a tough call for those without wealthy patrons.

Disgruntled members once leaked information about a car bought with EFF money and registered in the name of a third party: Voorsprong Trading, which was the name of Malema’s front company. A former Robben Island prisoner said he walked away from the party as it had become a “private company, a vehicle for the interests of a clique”.

‘Rent-seeking’ in metros where the EFF had coalitions

There are allegations in the book that the EFF would ask for government contracts in return for political support in metros where it was in coalition, such as Johannesburg and Tshwane. The party’s coalition with the Democratic Alliance in Johannesburg, with Herman Mashaba as mayor was a case in point.

In 2019, a turnkey electrification contract worth R229.5m was awarded to a company called F&J. A month later, Santaclara — a front company linked to Malema — received a payment from F&J. A few months later, the company secured another contract for LED streetlights, after which Santaclara again received a payment.

Officials involved are also said to have received kickbacks for facilitating the contracts, while payments to Malema were described as rewards for his political protection. There were similar claims around a fleet contract in the city. The DA forced Mashaba to resign, with city officials calling his three-year tenure as mayor ‘a nightmare’ in which the EFF was given licence to raid city budgets as procurement systems were bypassed.

Anyone for a lifestyle audit?

Malema’s taste for designer clothes and watches exceeds what a parliamentary salary of R125,000 a month can cover. Beyond his property portfolio, he travels in style. Neighbours say he sometimes arrives at his Palmietfontein farm — transformed into a luxury estate with a large house, pool, and basketball and tennis courts — in a rented helicopter. The farm is held through his Ratanang Trust.

The book details how money flowed into Mahuna Investments, a vehicle said to bankroll Malema’s lifestyle. The company paid no taxes and showed no real business activity, yet covered his son’s school fees, rent and pool costs at a Sandton home he moved into in 2011, as well as tailored suits and political campaigns.

Malema used a Mahuna Investments bank card at events such as the Durban July in 2017 and 2018, birthday parties and other celebrations. The card also covered Gucci and Louis Vuitton shopping sprees at Sandton City on the same day he addressed the EFF’s student command in a budget Johannesburg hotel.

Hate speech and shooting guns

Outside its focus on Malema’s finances, the book does not cover his criminal and hate speech cases. His chant of ‘Kill the Boer’ forms part of a wider picture that prompted US President Donald Trumpto impose a 30% levy on South Africa — higher than on any other African country.

In August, the equality court ruled it to be hate speech even though the high court said the historical roots of this chant means it’s not. He was also charged with contravening the Firearms Control Act in 2018 where he allegedly fired a rifle during an EFF birthday rally in Mdantsane, outside East London, an event that was captured on video. Malema maintains it was a toy gun and didn’t contain live ammunition. The judgment is expected on Tuesday 30 September.

(The Africa Report)