News

The Future Of Medicine In Nigeria Is Private – Dr Maryam Dija Ogebe

Doctor Maryam Dija Ogebe is reputedly the first female medical doctor from northern Nigeria. She studied at the University of Lagos College of Medicine, where she graduated in 1971. After specialist courses in anesthesia, she worked in many hospitals in Plateau and Benue states. She rose to the position of a chief consultant anesthetist in the General Hospital, Makurdi in 1983. She was in medical administration, as the chief executive secretary of the Benue State Health Management Board from 1987 to 1991, from where she retired. She has continued to work as a consultant in many private and public hospitals and charity organisations in Nigeria and abroad. The day of this interview, January 21, 2026, happened to be her 82nd birthday.

You are one of the first female medical doctors in northern Nigeria; What were the challenges you faced?

SPONSOR AD

Retrospectively, one can now look at the difficulties and challenges, but back then, I had no idea what I was going to become. All I knew was that my parents sent me to school and I enjoyed going to school.

The challenges were big. First, there was no school – primary or nursery school in Tilden Fulani – where I grew up. There was no schooling, but my dad could read and write. He had written down my birthday, and as if he knew that he would soon die, he appealed to my mom not to remarry but stay and look after us and educate us.

How many of you were there before he died?

Three: myself and two boys. One was six years younger than me, the other 9 years younger. My mother had to feed us, clothe us and send us to school. There was no school in the village, so we went 20 miles across the hills to Fubor.

We walked over the hills, down to rocky areas in Jarawa land twice a month. We took our goods, including garin dawa (ground corn) and gishiri (salt) to enable us cook there. After two weeks, our parents brought us more; and after one month, we would go back home and bring more.

That was in primary school?

Yes. We were just seven, eight and nine years of age. That was tough, but it was worth it because where there is the will, you will do it.

You attended a well known school – Gindiri Girls’ High School; was that difficult?

It wasn’t well known. I was in the second set, so it was just coming up. What happened was that after junior primary school in Fubor, I needed to go to a senior primary school, which had classes five, six and seven. There was one in Dass, which was another long trip.

They put me up with a family that had children of my age. We went to school and I did very well. At the end of senior primary school, they asked me to sit for an exam to go to Gindiri Secondary School; which I did. When I got there, the first set had started, so I was in the second set.

Was it on scholarship?

No. Anyone who felt pity helped. Of course my mum did most of it, but people helped. People from nowhere who didn’t know me or my mum felt there was a need – that there was a child who was doing well and her father was late, so ‘let’s give her a scholarship, pay her school fees and buy her books.’

Who gave you the scholarship?

I didn’t know most of them, but it was happening. The first government scholarship I got was in 1966 when I was admitted into the College of Medicine in Lagos. That was my first experience of a scholarship.

You went to Queen’s College, Lagos, a girls’ school, for your Higher School Certificate because you did well in Gindiri?

Yes. That’s another one that surprises me. When I was in Gindiri, I didn’t know what I was going to study for quite a long time until maybe in form three or so when one of my classmates said, “Since you are doing so well in mathematics and science, why don’t you study medicine?” It just clicked and I said yes.

My dad died an unnecessary death. So I decided to go and find out how people could live.

Also, my Mathematics and English teacher, Shelley Palmer, an English lady, was the principal. And she was interested and said, “But you can’t study medicine without taking Biology, Physics and Chemistry. So let me see what I can do.”

When I got to Queens College, I did the three subjects – Physics, Chemistry and Zoology – and passed to go to College of Medicine; in fact, any medical school. There were only two of them then: Lagos and Ibadan. Lagos was also brand new. The first set was just about to finish – they were in year five and we were coming in year one. For me, that was another big miracle.

How challenging was it for you to move from Jos to Lagos as a student? Who supported you? Was there a scholarship or it was still private individuals?

My mum and some of her relatives teamed up paying for my movements here and there. From Jos, I travelled by train. The train system was very good at that time. The train would go from Jos through Kafanchan to Kaduna, and Kaduna, to start going southwards through the South-West down to Lagos. I went on my own. People were very kind and conscious of children and helped them.

Were you not afraid or felt insecure?

No. At that time, there was nothing to fear, seriously, because unless you were carrying money or you were very rich and people would look for you. There were no human sacrifices and looking for money like now.

The worst anybody could do in those days was just to elope with a girl and say they were going to marry. That’s all.

After Gindiri, where you did well, was there pressure to marry, stay and teach rather than fly off to Lagos?

There was no pressure. Occasionally, when my mum wanted people to help, even among her own relatives, maybe she would say she wanted a loan because this girl was going to school and she needed money for this or that.

They would say, ‘Why are you wasting time on this girl? Look after the two boys coming after her. Save your energy educating her. This one will just go and get married and stay in somebody else’s kitchen. She won’t even help you.’

Then of course, by the time I got to Gindiri, I was more exposed to great help. There were some of my schoolmates who had come from well-to-do homes, some in Zaria. You know the Kitchener family – the children were my schoolmates. One was my senior, one was my immediate junior; and we became very friendly.

And this was a family where the children were not first generation but second or maybe third generation to go to school. So they looked at few of us who came from villages with very poor backgrounds. Being poor means there was no ready cash. There was something to eat and survive but no cash to pay school fees. So, some of them helped us and got their relatives to support us.

From this village background you suddenly found yourself in Lagos; how was the experience?

Again, Helen Kitchener, one of the daughters, who was my senior, was close to me. She was our first head girl. She was in the first set while I was in the second set. And she had relatives in Lagos. Mrs Margaret Olowu, who lived in Lagos, immediately became my guardian through the arrangement of my friend, Helen. Steve Kitchener was also in the first set of the College of Medicine. He graduated as a doctor when I was going to my second year. Also, there were some classmates of my husband who had gone from Government College, Keffi to the College of Medicine to study. And of course, a northern girl coming to read medicine. Everybody was excited!

So, all the northern males in the College of Medicine were ready (to help) me with their books, dissection sets, anything I needed.

There were (other) girls – 10 of us in the class, all from the South-West, South-East and Mid west.

Nobody from the North?

None. In fact, thanks to Dr Sadiq Wali, the physician to all the presidents in the country. He was in that first set. He was four years ahead. They all welcomed me, and after some months, Sadiq called me and said, ‘Maryamu, when you graduate you will be the first northern girl to qualify as a medical doctor.’ I asked if that was so and he said yes.

He said, ‘There’s a girl in either Romania or Bulgaria – one of these eastern countries – who was studying medicine, but she is a year behind you, so you are going to be the first.’ She was Dr Fatima Balla. I hadn’t met her, but I heard about her and read about her. I think she was around, in Kano or Abuja.

So, it was Sadiq that kept me informed. He also was an ex-Keffi student. So there were all those connections with my husband’s schoolmates.

Did you meet your husband before you went to Lagos for this medical sojourn?

I met him when I was in the last few years of my secondary school. He finished his Higher School Certificate (HSC) and came to the boys’ school to teach. He went to read Law, while I went to read Medicine.

Did you marry before you became a medical doctor?

Certainly not. I married during my own course because of his shorter course – he finished earlier. I got married when I had done three years in the medical college, and in the remaining two years, I got married.

Was it the experience in Queens College that spurred you to stay in the University of Lagos to read Medicine?

Yes. I reasoned that I had come to the South-West, where I didn’t understand the language, although everybody spoke English. I didn’t want to start learning how to live in Ibadan; and I really didn’t have many people there. It was Lagos that I knew. I knew the Kitcheners and few other people. I also didn’t know the bus routes. So, to avoid the stress, I decided to stay in the University of Lagos. I got admission into both universities.

I imagine that your movement had to tally with your husband’s since he was already a lawyer. Did you start working in Jos as a clinician?

Yes. When I graduated, I came to Jos to do my internship. I also had my first child there before I started looking for specialisation, which took me some time to do. It was quite sticky trying to specialise, I couldn’t do the specialisation in Jos.

Jos was just a general hospital with some Indian and Egyptian doctors. There was no teaching hospital, so to get retrained or proceed with postgraduate training, I would have to go elsewhere – either back to the South or outside the country.

And you went to England?

I went to England because I wanted to do the fellowship but found that with a young family, I needed to be at home with my children. I mean I had the first and second children. The younger one was just 11 months when I left home. And as if to really “show me pepper”, one day when I called to find out how they were doing, I was told that Eni( my daughter) had a scorpion sting the night before. You can imagine a mother hearing that!

I went to my bed and I cried, saying the next time they would say a snake had eaten this girl. From there, I started making my way to do the diploma and get back home.

You continued in Ibadan, isn’t it?

Yes. I came back to Ibadan and they took me for the diploma and I took the children along with me. I had a flat as a staff member doing postgraduate studies. It was easier and I could wind it up in 10 months.

Was it a deliberate decision for you to work only in government hospitals?

Yes. At that time, there were no private hospitals that could take a specialist; you either set up your own hospital if you were already qualified for it or you stay with the government. For example, for me to practice anesthesia, there had to be a surgeon. There was no indigenous surgeon. You need money to set up your own practice etc; and there were thousands of people who needed that kind of treatment. So we were more or less destined (for) government service.

Most of it was in Benue because you had to spend time with your husband?

When we got married, it was Benue-Plateau State, and he came from Benue and I was a Plateau person. When the states were created and we were moving, each person had to go to where our husbands belonged. I think they even placed us on contract. I think all married women were contract officers; that kind of thing. It was a challenge that was reversed later.

Did you feel it impacted your career, such that you couldn’t really reach where you wanted because of state constraint?

No. In fact, both states were at the same level, so if I had stayed home, wherever I could rise to in Benue State, I could also have risen in Plateau. The only thing was that I couldn’t take up government political appointments because I was remotely positioned. I couldn’t stay in Makurdi and do such a thing in Jos, and I couldn’t leave my family because of a political appointment.

And in fairness, I was always given what was due to me in Benue State, even more than my husband would have because there was a lot more discrimination against him than me.

You became the chief consultant of the general hospital and the chief executive of the Health Management Board. I thought that was political in a way?

It was professional. First, I was the chief consultant in charge of the general hospital – a 300-bed hospital. That was a big, hectic job. Then I became the chief medical director of the Health Services Management Board before I became the executive secretary. These are all regarded as administrative. If I had been appointed a commissioner for health, it would have been political.

When you retired in 1991; was that not too early? Did you feel that professionally you could not go beyond the Health Management Board executive?

It wasn’t the bar. I could have stayed on the board for several years; there was nothing biting me. I could have been appointed commissioner for health and that would have been political. And I could have sought my exit from there.

The reason I retired early was because my husband’s name had been sent to the Military Council, to be appointed as Justice of the Court of Appeal. He had marked many years in the state service and some of his juniors had been moving above him. It was time for him to move and I was preparing the ground to move with him, because he had made it very clear that he never planned to have his family split – wherever he moved, his family would move with him.

So, from 1991 you had to move with him to Benin, Plateau and those places?

Yes; but not much of Plateau. The movement was, first of all to Edo State, then Kaduna; from Kaduna to Port Harcourt, Lagos and Abuja; then from Lagos to Enugu and Abuja.

I noticed that from then on, your energy went more into voluntary activities – charity work?

Yes. I was taking up part-time jobs, which I humorously called doing “kabu-kabu doctor work.” I took up jobs with people who were settled – they had their own clinics going and I could take up a job with them as a general person or an anesthetist, whichever one they needed.

Would you say the “kabu-kabu doctor work” was rewarding?

It was rewarding in a way that since I qualified, I had been working for the government, but this time, I started working in the private sector. It was a new place of learning to be able to attend to patients from an angle where they would be heavily charged, an angle where they could insist on knowing why they were being treated in a certain way and why they were receiving the injection; how they were inspected.

So, I entered into a kind of marketplace of medicine, whereas before, it had been the government checking you, and your patients hardly had any feedback. In fact, my first private place was in Benin City, where after about three years, not just in hospital practice but experience of the world, I discovered that if you lived in that city you had to come out with a certificate you awarded yourself, for having learned a lot about life.

You lived in Lagos and abroad, why was Benin very special. What particularly struck you?

Benin was special because in what we knew as Bendel in those days – now Delta and Edo – we northerners were known as docile and mild people you could twist anywhere – or they were so sympathetic that they could help you to any extent. And you got to a group of people who were very wise. When I got to the hospital, for example, they pulled me aside and said, “Doctor, we know where you are coming from; we are nurses and we know your background. Please, as you have come to this city, we urge you, don’t trust anybody, not even us.”

It was good and kind of them to have told me. They said, “Look, if anybody comes here smiling, even if you know the person casually and they say look after my bag, I am coming, don’t agree because they could have hidden hard drugs there and they will set you up and you can’t get out of it.”

Apart from Edo, I also did medical “kabu-kabu” in Kaduna – at the NNPC clinic. Some private surgeons also engaged me for anesthetic cases around the town. There were not many, but I enjoyed them, seeing that the future of medicine in Nigeria should really not be government, it should be private. Even if the government is going to subsidise, when it is private, it is done more efficiently and cheaply.

Yet you never felt tempted to start a private hospital?

I couldn’t do that because of the family; I was going to move around. And look at a number of the justices in the Court of Appeal; they were moving quite often. The longest of his stay was three and a half years at a station. How long would it take me to set up a hospital, and when the husband was moving, he would say he must move with the wife. So what would I do with the hospital? It is not something you can easily sell to someone.

There are lots of cases where people go to hospital and maybe because of carelessness, there’s an overdose. Do you think that in general, there’s a problem with anesthesia in our country?

I have been out of anesthesia for 20 years now, so I am not an authority anymore. But some fields are open to overdose and carelessness more than others. For example, my husband had to have surgery for his prostate to be removed three or four years ago and it was in a private hospital. I was there from beginning to end. In fact, the surgeon was my junior when I was heading Makurdi General Hospital. He came, did his internship and eventually, we got him training in the UK, which he went and did. He specialised in surgery and came back to Nigeria. In fact, he is a very good hand.

We went to a private hospital because we could afford it. The hospital gave us their bill and he had the surgery successfully. Then, back in the ward, suddenly, he was losing a lot of blood. We looked for more blood and gave him, but he continued losing blood. Then the next bottle of blood was ready to be set up. The doctor tried to set up the blood but couldn’t. Anywhere he punctured, the vein would bleed. It now clicked in my head that the blood was not clotting. I said let’s get an emergency vitamin K and give him. We gave him vitamin K and within 30 minutes he was able to set the drip; the clotting was okay.

We started looking for the cause, which was that he had been on anti-hypertensive treatment, and along with that, you have to take mini aspirin to keep the blood thinning so that blood clots are not formed.

That mini aspirin was not discontinued. It was supposed to be discontinued two weeks before surgery. And his surgery wasn’t an emergency, so we could have stopped it. It escaped the doctors, it escaped my own mind.

I should have known, even if they missed it because I was the one in charge of his drugs. And of course, he could easily have bled to death or gotten complication from having blood transfusion.

So mistakes can happen; and they do happen, almost on a daily basis. Many of them could be counteracted if you were quite awake and looking at what is happening.

After medicine you went into a lot of Christian voluntary work – a long list – but I want you to say something about it. What is the motivation; are you still at it?

Yes. I went partly into conservative medicine or health care, as well as Christian work. The conservative health care I went into was when I discovered that there were a lot about nutrition and other things like exercise, rest, anti-stress and so on, which we don’t learn in medical school at all. I mean there is so much to study and learn in medical school, such that they consider it a waste of time to bring in nutrition and diet.

So this is lifestyle medicine?

Yes. But we just brush it aside as something you can read about later. So in retirement I thought: why not read and understand. I can check diaries and dictionaries; I can even go on Google and find these things out. But I found companies that were giving lectures and selling supplements that match with people’s particular needs – those with more stress than others, those with age problems or those with restricted diets.

Some people restrict themselves from a diet – they do not eat vegetables; they just don’t like it. Even if you put it in egusi or okro soup, you have to disguise it. So I decided to go into it and spread the message by giving voluntary lectures.

There was a time we formed a team and did that, and it was very rewarding. For Court Justices whose work involves just sitting down from morning till night. They had to learn how to stand up and get their own files.

They were told that apart from going to toilet, messengers and personal assistants do every other thing for them; and they were killing themselves. They have to be able to stand up, walk around and do this and that.

I also gave lectures on family health structuring. Then there is a body that cared for leprosy affected people and they no longer wanted us to call them lepers. They said they were leprosy affected people. There were two non-governmental organisations that looked after those unfortunate people and I was invited into the board of one of them, which I took up well.

I did two terms there and two terms on the international body of that particular non-governmental organisation, based in the UK. They held meetings every year in different countries, going round.

Since I love travelling, I really enjoyed being on that seat for nine good years. There’s a country I even went to twice – Sweden. I have been to Switzerland, Nepal, India and Thailand to hold meetings. Can you imagine?

Also to learn a lot, even from things like leprosy and know that it was still there and there were new cases. Every year, there are new cases coming up; and it is not easy to find out how it spreads. Somehow, 95 per cent of persons are immune to it, but you don’t know how to find the 5 per cent that are not. It is difficult.

What of the scholarship foundation?

People helped me, even when they didn’t know me, so I decided going to look for children that didn’t know me, whose parents probably were not alive and they were not going to school. Somebody was kind enough to house and feed them, so I would find schools for them.

I talked with my husband, who came from a background very similar to my own; so we agreed to set a foundation and support children from primary and secondary education only. We started with that when I turned 75. We launched it in 2019 and registered at the Corporate Affairs Commission (CAC). And quite honestly, it is wonderful. So many people are receiving help.

How much are you able to do?

That’s what used to dampen my spirit when I was younger. I would say the problems were many, what could I do? It was like I could not do anything, but with maturity, I know that I can do the little bit I am doing; and my doing it may inspire somebody else to also do.

If they had refused to help me because there were many children who needed help, I wouldn’t have got it, but they helped. Quite honestly, right now, we don’t have more than 100 on our platform, but they are happy and we are happy.

In fact, it gives me a very good reason to live on and look after the little I have, as well as detest unnecessary expenditure on myself, my house or anything when people are there suffering.

Your biographer said you are an unsung heroine who has not been recognised. You have no street named after you. Do you feel kind of under-appreciated by the society?

Not at all. In fact, when people complain and they try to push me, I say ‘don’t worry, it doesn’t matter, it doesn’t add anything or subtract anything from me.’

In fact, this one you are celebrating now – this first female (doctor from the North)- I was very silent about it. It didn’t bother me, but they kept bringing it up and I now I said, ‘okay, thank you, I will accept it.’ To me, it doesn’t add, it doesn’t subtract.

All in all, my responsibility to my maker is to listen to my heart and do what he has placed in my heart to do, unselfishly and as efficiently as I can. What is the efficiency? Being able to ask other people, to recruit people who will be able to support such a course, knowing that I will not eat out of it; I have enough food for myself. And I will not build a house out of it; I have a house already.

I am just doing this for people who have nowhere to cry to. To me, that’s better recognition than to be putting my name up and down and giving me all sorts of awards that I will just pin on the wall and it will earn nothing.

How is life in retirement? You and your husband are retired; how do you live through the day?

We have got a good regime. We have listened to a lot of advice about retirement. There’s a lot of advice about how you need to move, how you need to listen to your body and eat the right things. They say there are things you shouldn’t eat at this age. You just eat a little bit of it and be satisfied. Don’t deprive yourself completely, but at least don’t over indulge. And we are keeping that

We also found that doing good to other people is very rewarding for a retired person. You have to do good to other people.

And we exercise every day in fresh air – we go for a walk. We have these indoor exercising things too, but we prefer to go out. My husband is an extrovert, so for him, there’s no problem, but I am more of an introvert and I didn’t like going out in the streets.

I feel conscious that people are watching me through their windows and wondering why this old woman is walking about. But because of his nature I had to bury my own; and we are enjoying it.

How are the children, including the one bitten by a scorpion?

The children are doing well. The one bitten by a scorpion was in university. She was 21 about going to 22 when she was involved in a car crash and she passed away. So we have three remaining. The two boys are lawyers and married to lawyers. The girl is a medical doctor married to an engineer. The children are settled.

They are doing well; and thank God that they don’t have to look after us too much. We are on pension and pension is looking after us.

Do you still have the chance to do what you love doing – travelling?

Oh yes, we still travel. I love travelling. In fact, for my 80th birthday two years ago, the family wanted to throw a party and invite everybody and celebrate me, but I said, ‘you know what, I have been wanting is to go to Australia, give me a ticket to go to Australia.’ They said, ‘oh, you got it.’ So they arranged a ticket and both of us travelled to Australia for six weeks. I think we enjoyed it thoroughly.

Any other hobbies?

Reading and gardening. I have a lot to do with horticulture. I keep a lot of exotic plants. I like plants a lot and I take care of them. Yes, I read a lot. But nowadays, you know that almost all reading is on the phone, just on your palm. You can read everybody and everywhere. But I still read books.

(Daily trust)

-

Business10 hours ago

Business10 hours agoGas supply crisis cuts power generation to 3,940MW

-

News10 hours ago

News10 hours agoDetention: El-Rufai Petitions ICPC, Demands N15.6bn Damages

-

News10 hours ago

News10 hours agoDIG Mba, others retire, seven AIGs for promotion

-

Politics11 hours ago

Politics11 hours agoWe Will Adopt Tinubu As 2027 Presidential Candidate – APGA

-

Politics10 hours ago

Politics10 hours agoTinubu Elevates Masari To Special Adviser

-

News10 hours ago

News10 hours agoBorno: Hundreds still missing after Boko Haram attack

-

Sports10 hours ago

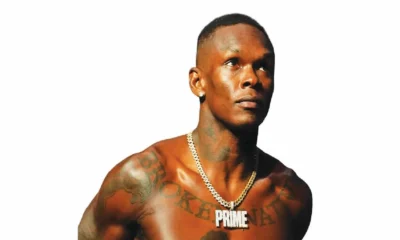

Sports10 hours agoAdesanya demands $15m per fight from UFC boss White

-

World News10 hours ago

World News10 hours ago‘They host US military bases used to attack us’ — Iran defends striking Gulf countries