Business

Capital gains tax testing investor confidence

Nigeria’s move to bring back capital gains tax on equity investments has gone beyond a routine fiscal discussion, revealing underlying weaknesses in the country’s capital market. As investors reassess risk, foreign participation wanes, and liquidity providers pull back, the policy prompts deeper questions about Nigeria’s capacity to align revenue generation with sustainable, long-term market growth, writes TEMITOPE AINA

The normally bustling trading floors were unusually quiet in November. Dealers who were once animated by ringing phones and fast-moving prices sat back, watching screens flicker with red. As Nigeria’s government prepared to restore capital gains tax on equity transactions for the first time in decades, investors, both domestic and foreign, paused, recalculated, and reconsidered their exposure.

The policy, which imposes a 30 per cent tax on profits above N150 million, was framed as a necessary revenue-raising measure at a time of fiscal strain. But in a market already weakened by years of volatility, currency pressures and fragile confidence, the announcement landed like a shockwave. For many investors, it was not just another tax; it was a signal that the cost of investing in Nigeria’s capital market was about to rise significantly.

At stake is confidence, the invisible currency that sustains financial markets. Long regarded as the stabilising force in Nigeria’s equities market, institutional and foreign investors are now openly questioning whether the country can still compete with other emerging markets where capital gains taxes are either minimal or non-existent. Each naira taxed from investment returns, some argue, is a subtle warning that the balance between risk and reward may no longer favour Nigeria.

Understanding the capital gains tax shift

The new framework for capital gains taxation represents one of the most consequential changes to Nigeria’s investment landscape in years. According to a PwC report, small companies, defined as those with an annual gross turnover of N100m or less and total fixed assets not exceeding N250m, are exempt from companies income tax, capital gains tax and the newly introduced development levy.

For larger companies, however, the changes are significant. Under the Nigeria Tax Act, the capital gains tax rate for companies has been increased from 10 per cent to 30 per cent, effectively aligning it with the Companies Income Tax rate. The aim, according to policymakers, is to eliminate tax arbitrage between chargeable gains and trading income.

Individuals are also affected, with capital gains now taxed at applicable personal income tax rates based on progressive income bands. The law further introduces capital gains tax on indirect transfers of shares in Nigerian companies, meaning that offshore disposals of intermediary holding companies can trigger Nigerian CGT, subject to applicable tax treaty exemptions.

At the same time, the exemption threshold for share disposals has been raised from N100m to N150m within any 12 consecutive months, provided total gains do not exceed N10m. On paper, these measures appear targeted at high-value transactions. In practice, they have ignited a far-reaching debate over Nigeria’s competitiveness as an investment destination.

That debate is now playing out across trading floors, boardrooms and policy circles, as investors and capital market operators ask a fundamental question: Is Nigeria still the best place to grow capital?

Investors react, markets respond

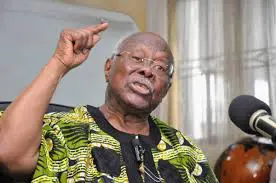

The Federal Government’s reinstatement of capital gains taxes immediately introduced caution into the market. Some investors began exiting positions, others paused new investments, and many waited for clarification. For Ayokunle, a veteran capital market operator, the reaction was predictable.

“The issue with the capital market and capital gains tax is that it is a tax on the gains you make from your investments, particularly equities,” he explains. “Most emerging markets either do not apply this kind of tax, or where they do, it is very minimal. That difference immediately changes investor behaviour.”

Foreign investors, who have played a critical role in stabilising Nigeria’s foreign exchange market in recent months, are especially sensitive to such shifts. According to Ayokunle, some have already begun to pull out, while others are holding back until the policy environment becomes clearer. “For every significant profit an investor makes, the government now takes a percentage, and that changes the return calculation,” he says.

Nigeria, he notes, is not operating in isolation. It is competing with markets like Ghana and other emerging economies for the same pool of global capital. “If those markets are more attractive, investors will simply go there. That is why people are concerned about how this policy will affect the capital market, particularly in the short term.”

The mechanics of the tax itself are straightforward. It applies to profits exceeding N150m from the sale of stocks, with the burden falling squarely on investors rather than brokers or market operators. “Stocks are assets,” Ayokunle explains. “When you buy them and later sell at a higher price, the profit you make is what is being taxed.”

From the government’s perspective, the rationale mirrors other forms of taxation. “If you earn a salary, you pay PAYE. If a company makes a profit, it pays corporate income tax. So, the argument is that if an investor buys an asset and resells it at a higher price, the government should also collect tax on that gain.”

Yet the distinction between domestic and foreign investors is critical. Domestic investors, whose funds are already within the Nigerian system, have fewer alternatives. Foreign investors do not. “Many emerging markets either levy no capital gains tax or apply it at much lower rates,” Ayokunle notes. “If Nigeria introduces a tax that competing markets do not have, investors will naturally prefer those other markets.”

Market data appears to support this concern. November marked one of the stock market’s worst performances of the year, driven largely by uncertainty around the new tax regime. Although the government later issued clarifications, the initial fear had already taken its toll on sentiment.

One major concern was whether gains accumulated over many years would be taxed retroactively. Investors who bought shares a decade ago at low prices worried they would face large tax bills on long-held positions. The government clarified that the market value as of 31 December 2025, would serve as the cost base, meaning only gains accrued after that date would be taxed. Profits below N150m remain exempt.

There is also a provision allowing investors to defer payment by reinvesting proceeds into another equity investment within a specified period. This, Ayokunle believes, could encourage gradual exits rather than sudden sell-offs, as investors manage their exposure while keeping funds within the market.

Still, he sees the policy less as reform and more as fiscal necessity. “This is about revenue generation,” he says. “The Minister of Finance has been clear that the government is struggling to raise revenue and is looking for innovative ways to do so. This policy is driven by that need, not by a broader capital market development agenda.”

When foreign capital hesitates

Foreign investors stayed on the sidelines in November 2025, with equity trades on the Nigerian Exchange Limited remaining below N200bn for the second straight month. While foreign participation fell 13 per cent to N162bn, domestic investors dominated the market, driving total trades to N971 bn and keeping the bourse vibrant. Institutional investors led the charge, outpacing retail activity and helping year-to-date transactions hit a robust N10.54tn, underscoring the growing strength of local capital in Nigeria’s stock market.

Foreign investors maintained a cautious posture in Nigeria’s equity market in November 2025, as total foreign equity transactions on the Nigerian Exchange Limited remained below N200bn for the second consecutive month, reinforcing signs of subdued offshore participation amid persistent macroeconomic and currency-related concerns.

According to data contained in the NGX Domestic and Foreign Portfolio Investment report, foreign equity trades declined by 13.17 per cent month-on-month to N162.04bn in November 2025, compared with N186.62bn recorded in October 2025. The sustained sub-N200bn performance over two consecutive months points to a prolonged moderation in foreign trading activity on the Exchange.

In dollar terms, foreign equity transactions dropped from about $131.27m in October to approximately $112.00m in November, reflecting both reduced trading volumes and the impact of exchange-rate movements at the Nigerian Autonomous Foreign Exchange Market.

Overall market activity declines month-on-month

Total market transactions on the NGX also recorded a decline during the review period. Aggregate equity trades fell by 5.95 per cent to N971.18bn in November 2025, down from N1.03tn in October 2025.

Despite the month-on-month contraction, market activity showed strong year-on-year improvement. When compared with the N442.34bn recorded in November 2024, total transactions in November 2025 represented a 119.56 per cent increase, highlighting a broader recovery in trading volumes over the past year.

Informal levies and trust deficit

Beyond formal taxation, investors also point to Nigeria’s wider fiscal environment. Ayokunle notes that many Nigerians already bear the burden of informal levies and unofficial charges, creating a sense that the tax system is neither fair nor efficient.

“There is a widespread perception that government revenue is not being used efficiently,” he says. “In countries where taxes are higher, people are more willing to pay because they see the benefits. In Nigeria, that confidence is lacking.”

That trust deficit feeds fears of capital flight. In November, market losses were so severe on one trading day that regulators grew concerned that trading might have to be halted. “Some foreign investors have already moved funds out,” Ayokunle says. “Others are reconsidering their positions. Since Nigeria is competing with markets that have lower or no capital gains tax, investors will gravitate towards those alternatives.”

Returns, inflation and double taxation

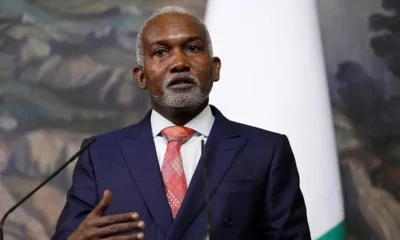

For Charles Sanni, Chief Executive of Cowry Treasurers Limited, the impact of capital gains tax is best understood through its effect on returns. “The burden of capital gains tax clearly falls on the investor,” he says. “The broker is merely a collecting agent, except where trading on a proprietary account.”

The arithmetic, he explains, is unforgiving. “If you earn a 10 per cent return and pay 30 per cent capital gains tax, what remains is seven per cent. Investors then compare that with inflation. If inflation is 18 per cent, that investment makes no sense.”

From a competitiveness standpoint, Sanni questions Nigeria’s position. “I am not sure many countries in Sub-Saharan Africa impose capital gains tax in this way. If Nigeria proceeds while competing markets do not, foreign investors will simply go where returns are better.”

Foreign investors may also face double taxation, paying tax in Nigeria and again in their home countries. While increased revenue could, in theory, fund infrastructure and capital expenditure, Sanni warns that implementation is crucial. “Any tax must not be so punitive that it encourages avoidance. If investment flows fall, foreign exchange earnings decline, reserves weaken, and the balance of trade suffers.”

He argues that the tax disproportionately affects high-net-worth individuals, institutions and foreign portfolio investors, the very groups that provide depth and liquidity to the market. “Rather than repeatedly taxing the same group, the government should broaden the tax net. That is far more sustainable.”

Market behaviour under pressure

Teslim Shitta-Bey, Chief Economist and Managing Editor of Proshare, places the debate within the broader theory of market behaviour. When investors believe alternative instruments such as Treasury Bills or commodities offer better returns, they shift gradually, allowing markets to function normally. Trouble begins when exits become simultaneous.

“If everyone is dumping equities at the same time and there are no buyers, prices keep falling,” he explains. “Panic sets in, and that is how markets collapse.”

For retail investors, the immediate impact of capital gains tax may be limited, as most do not generate gains anywhere near N150m. Institutional investors, however, will feel the impact when they sell to meet obligations. Even then, Shitta-Bey notes, many large shareholders hold long-term positions and rarely sell.

From the government’s perspective, diverted funds may simply flow into government securities, helping to finance the budget. But Shitta-Bey argues that taxation should not be the default solution when Nigeria has significant idle assets. Partial listings of state-owned enterprises, such as NNPCL, could raise substantial revenue while deepening the market and broadening ownership.

He cautions against direct comparisons with other countries. Nigerian businesses, he notes, bear costs for power, water and security that governments elsewhere provide. “When businesses succeed despite government, taxation becomes difficult to justify,” he says.

Liquidity, capital flight and historical lessons

For Tajudeen Olayinka, an investment banker and stockbroker, the real danger lies in how the tax effects liquidity providers, mostly institutional investors who trade actively and absorb market shocks. “Without them, liquidity risks for other investors increase significantly,” he says.

These investors constantly reprice securities to reflect future risks. As a result, even investors below the tax threshold indirectly bear the cost through lower valuations. Olayinka recalls that Nigeria’s earlier 10 per cent CGT was suspended precisely to allow the market to mature. “Has the market developed sufficiently to justify 30 per cent CGT now? I do not think so,” he says.

That concern is echoed by David Adonri of Highcap Securities, who describes the policy as a potential turning point. “CGT was suspended in the 1990s to make the market competitive,” he recalls. “Reintroducing it at 30 per cent came as a surprise.”

Adonri warns that while the tax may raise revenue, it risks undermining market growth. “It penalises investors and discourages capital formation,” he says. “A developing economy like Nigeria, which needs enormous capital, should not pursue a policy that drives investors away.”

A delicate balance

At its core, Nigeria’s capital gains tax debate is about balance: between revenue and growth, taxation and competitiveness, short-term fiscal needs and long-term market development. The policy has exposed deep anxieties within the investment community and highlighted the fragile trust between government and capital.

Whether the tax ultimately strengthens public finances or weakens investor confidence will depend not just on rates and thresholds, but on consultation, implementation and the broader economic environment. For now, the silence that fell over trading floors in November speaks volumes about a market waiting, uneasily, for clarity, reassurance and direction.(Punch)

-

World News21 hours ago

World News21 hours agoIran Confirms Supreme Leader’s Death As Attacks Continue

-

Politics21 hours ago

Politics21 hours agoNigerians Are Hungry, Will Shock You In 2027 – Bode George Tells APC

-

News21 hours ago

News21 hours agoFG Issues Advisory To Nigerians In Middle East

-

World News21 hours ago

World News21 hours agoAyatollah Ali Khamenei: The Leader Who Shaped Iran’s Defiance

-

Opinion20 hours ago

Opinion20 hours agoReflections on FCT polls and voter apathy

-

Metro21 hours ago

Metro21 hours ago‘I won’t be bullied’ – Seyi Tinubu addresses VDM’s claim of secretly funding King Mitchy’s charity work

-

News21 hours ago

News21 hours agoTinubu Renews Tenure Of Audi, NSCDC CG

-

News21 hours ago

News21 hours agoLassa Fever Kills 10 Health Workers In Benue