Politics

2027: Can City Boys buy over Village Boys?

Nigerian youth involvement in politics is getting a new makeover ahead of the 2027 general election. On one side is the freshly relaunched City Boy Movement and on the other side is the newly unveiled Village Boy Movement. And somewhere in the middle is the undecided Nigerian youth, scrolling through X (formerly Twitter), wondering who is selling hope and who is selling hype.

The latest political youth drama was triggered by the relaunch of the City Boy Movement by Seyi Tinubu, the son of President Bola Tinubu in the Southeast — a region where President Tinubu recorded one of his weakest performances in the 2023 election.

For many political observers, that move alone shows how seriously the Tinubus and the ruling All Progressives Congress are now taking the Southeast youth space.

Enter the Southeast billionaires

The City Boy relaunch got more attention when well-known business figures from the Southeast joined in to take the campaign to the heart of the region.

Among those publicly aligned with the movement are nightlife entrepreneur, Obi Iyiegbu, popularly known as Obi Cubana and his fellow night club owner, Pascal Okechukwu, also known as Cubana Chief Priest.

In a clear show of structure, Seyi recently announced Cubana as the South East Director of the movement, while Chief Priest was named the Imo State lead.

Not long after, campaign-branded buses were unveiled.

The buses, donated by the Southeast young billionaires are meant to move across the region’s five states for grassroots mobilisation and political outreach in support of Tinubu’s 2027 re-election bid.

With the new buses, the City Boy Movement plans to feature empowerment rallies and give out thousands of tricycles (Keke Napep), cars, and other items to young people in the Southeast.

In short, it’s a mix of mobilisation, logistics, and giveaways.

In Nigerian politics, this kind of combination is usually intentional.

A calculated return to the East

Politically, the Southeast has been one of the most difficult regions for the APC since 2015. In 2023, the region overwhelmingly backed Peter Obi, a native of Anambra State and the most popular political figure among young voters in the zone.

Obi is now aligned with the opposition African Democratic Congress and remains the rallying point for the Obidient movement.

While the APC has won over all the governors in the region, the City Boy expansion into the region is about softening youth resistance.

But money, buses, and promises of empowerment alone may not win the Southeast youth vote. That lesson was painfully clear in 2023.

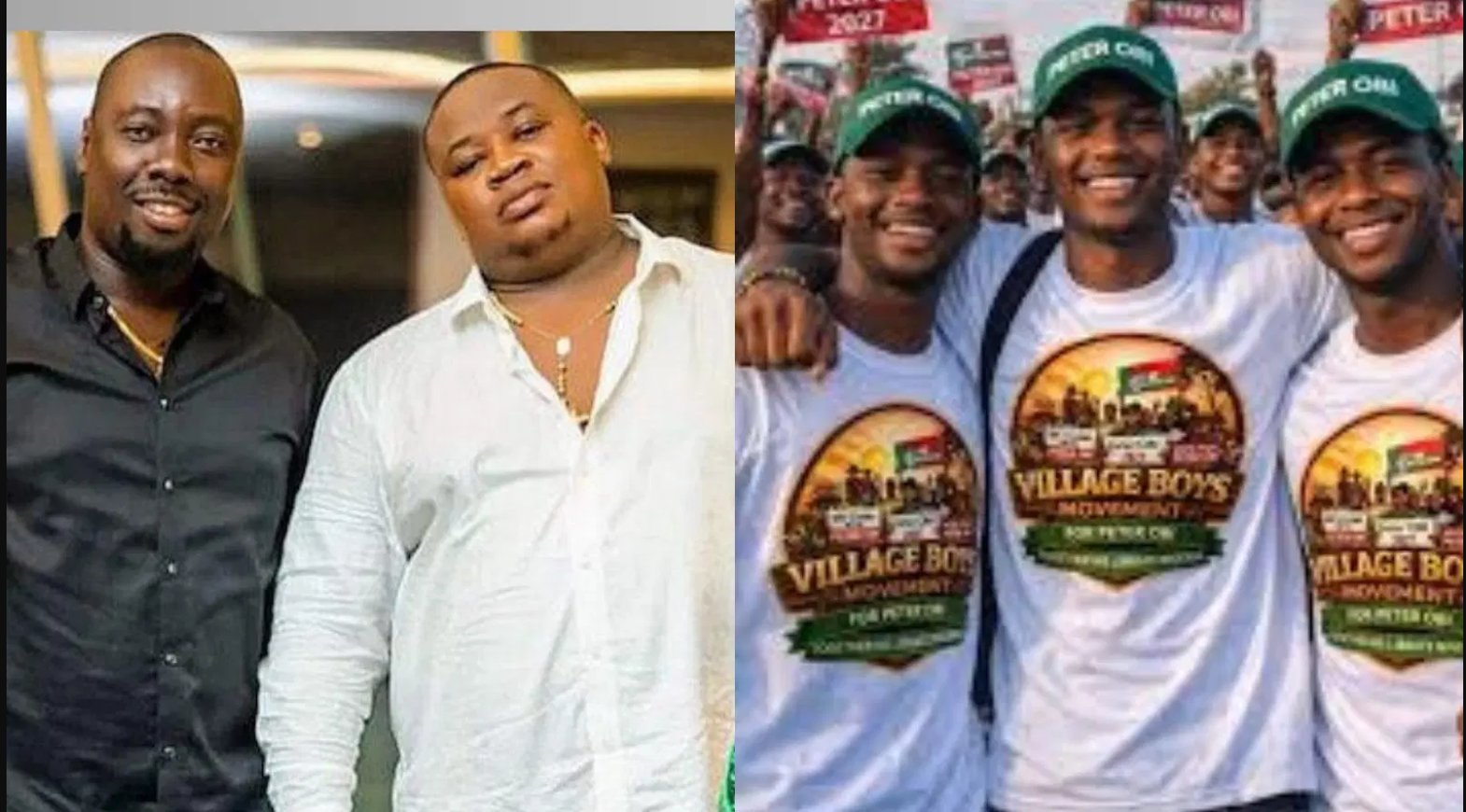

The birth of the Village Boy Movement

Predictably, the Obidient camp did not watch quietly.

To counter the City Boys’ incursion into the South East, Obi supporters unveiled a rival youth platform, the Village Boy Movement, in Abuja.

The convener of the group, Tochukwu Ezeoke, who calls himself the “Village Headmaster”, says the movement stands for “a Nigeria that works before it earns and earns before it spends.”

It is a subtle but pointed jab at what supporters describe as elite-driven, money-powered politics.

Unlike the City Boy Movement, which wears its billionaire backers proudly, the Village Boy project presents itself as organic, volunteer-driven and digitally mobilised.

No big donors. No bus unveiling ceremonies. No convoy culture.

Just hashtags, WhatsApp groups, volunteers and emotional attachment to Peter Obi.

The Village Boy follows Obi’s well-known “we-no-dey-give-shishi” political philosophy — meaning no financial inducement, no transactional politics.

Two styles, two worldviews

At its core, the City Boy versus Village Boy rivalry is not just about campaign branding. It reflects two sharply different political worldviews.

The City Boys represent elite-supported political organising — structured, funded and designed to scale quickly through physical mobilisation, logistics and welfare distribution.

The Village Boys represent populist digital mobilisation — emotionally driven, volunteer-powered and heavily dependent on online influence and community networks.

One side believes the organisation requires money. The other believes belief is enough.

One side speaks the language of empowerment programmes. The other speaks the language of moral protest.

In Nigerian politics, both methods have succeeded and failed at different times.

Can money really change the youth vote?

For many youths in the Obidient camp, Peter Obi is not just a politician. He is an identity. He represents frustration with elite politics, anger at ‘structure of criminality’ and a generational demand for discipline and competence.

The Obidient movement thrives less on party structure and more on emotional ownership.

This makes it hard for a movement that depends on elite endorsements to gain ground.

However, dismissing the influence of City Boys in the Southeast as irrelevant would also be politically naïve.

Money still matters. Visibility matters. Repeated engagement matters.

The City Boy strategy appears designed for the long game — slowly normalising APC presence among youth groups, sponsoring events, creating peer influencers and reducing political hostility, not necessarily flipping voters overnight.

In other words, it is less about immediate conversion and more about political rebranding.

As 2027 approaches, Nigeria is likely to witness a noisy contest between these two youth brands.

The City Boys will campaign with logistics, empowerment programmes and celebrity influence.

The Village Boys will campaign through digital activism, emotional storytelling, and constant references to Obi as the symbol of “a new Nigeria”.

It will be money versus momentum. Convoys versus conversations. Campaign buses versus campaign threads.

Most importantly, this will test whether political loyalty among Nigerian youths can be bought or if it has to be earned through persuasion.

In Nigeria, money can open doors, but can the City Boys open the hearts of the Village Boys especially in the Southeast to embrace the APC?

That is a question only time can answer. (Vanguard)

-

World News22 hours ago

World News22 hours agoIran warns US bases, assets legitimate targets if attacked

-

Business22 hours ago

Business22 hours agoTikToker Khaby Lame’s $975 million deal is riding on a crashing stock

-

Opinion23 hours ago

Opinion23 hours agoWale Edun: Architect of Nigeria’s fiscal and monetary stability honoured abroad, unsung at home

-

News23 hours ago

News23 hours agoNigeria’s public debt stock rose by N900bn to N153trn in Q3 2025 – DMO

-

Metro8 hours ago

Metro8 hours agoWhy my people hate Nigerians — South African beauty queen, Ntashabele

-

News8 hours ago

News8 hours agoWorld Bank to approve $500m Nigeria loan March

-

Business8 hours ago

Business8 hours ago“A ₦6.5 Trillion Blackout”—Tinubu Under Fire as GenCos Allege ₦4tn Debt Recovery Fund Has Been ‘Balkanised’ by Advisers

-

Business8 hours ago

Business8 hours agoLagos enforces 5% tax on gaming winnings