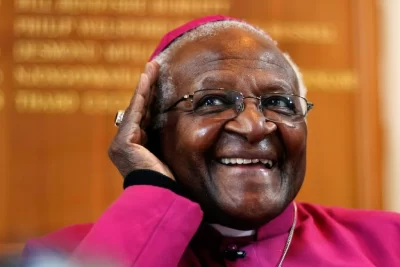

OBITUARY | Desmond Tutu: Tenacious, charismatic, and a thorn in the National Party and ANC’s side

A tireless social activist and human rights defender, Tutu not only coined the term “Rainbow Nation” to describe the country’s ethnic diversity but, after the first democratic elections in 1994, went on to become its conscience, using his international profile in campaigns against HIV/Aids, tuberculosis, poverty, racism, xenophobia, sexism, homophobia and transphobia, among others.

His was a powerful, forthright voice, one that irked both the Nationalist government and its successor, the African National Congress and its allies.

‘I wish I could shut-up. I can’t’

He was, an activist noted, “given to expressing his opinion in ways that are guaranteed to be outside the realm of comfortable politics”.

As Tutu himself put it, in 2007, “I wish I could shut up, but I can’t, and I won’t.”

It was that tenacity, particularly as an opponent of apartheid, that first catapulted the charismatic Tutu to prominence. With the ANC then a banned organisation and its leadership either exiled or imprisoned, the role of speaking truth to power was one that fell to community leaders like the clerics; as an Anglican archbishop, Tutu grasped the opportunity with dynamism that endeared him to many South Africans.

In 1986, at the height of PW Botha’s crackdown on dissent, Bishop Michael Nuttall, then head of the Natal diocese, explained Tutu’s role thus:

“This dynamic, diminutive man has made himself available because others asked that he should, to be a light in the darkness and to help lead us into the dawn of a new day.”

He was a born orator and, according to the journalist Simon Hattenstone, “a natural performer [with] his hands and eyes flying all over the place, his voice impassioned and resonant; a tiny ball of love.”

Tutu would often play down such adulation. “I was,” he once said of his reputation, “this man with the big nose and the easy name who personalised the South African situation.”

Such self-deprecation was typical of his humour, which he freely used to leaven the otherwise sombre gatherings and rallies he addressed. A favoured joke was about foreign diplomats taking a helicopter ride with Botha and his police minister, Adriaan Vlok. Flying over the Limpopo River they spot “the Arch” on waterskis being towed by security policemen in a boat. The diplomats express surprise that the cleric and the white cops could be enjoying such recreational fun together, whereupon Vlok whispers to Botha, “These foreigners don’t know a thing about hunting crocodiles.”

Truth and Reconciliation Commission

At times, though, the spiel irked more curmudgeonly commentators, like journalist Ken Owen, who once noted, “The archbishop has an unerring instinct for schmaltz, for the tear on the cheek of the child, for the single raindrop in the rose.”

Tutu’s finest hour came when he chaired the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which was set up to bear witness to, record and in some cases grant amnesty to the perpetrators of apartheid-relation human rights violations, as well as rule on reparation and the rehabilitation of victims.

“The truth,” Tutu had warned ahead of the first hearings in April 1996, “is going to hurt.” And it did; on the TRC’s second day, Tutu himself broke down, weeping, while listening to a victim describe how he was tortured by security police.

“I could not hold back the tears,” he said.

“I just broke down and sobbed like a child. The floodgates opened. I bent over the table and covered my face with my hands. I told people afterward that I laugh easily and I cry easily and wondered whether I was the right person to lead the commission since I was so weak and vulnerable.”

Tutu was so mortified that the media had focused on his emotions rather than victims’ testimony that he resolved to only weep at home or at church – and not at the hearings. He remained deeply disturbed by the stories of anguish and suffering of the witnesses but expressed amazement that many victims were not consumed by hatred and were willing to forgive their torturers.

One of the TRC’s key accomplishments was to uncover apartheid crimes that had been shrouded in secrecy. For example, Adriaan Vlok had testified that it was PW Botha who had ordered the 1988 bombing of Khotso House, the headquarters of the South African Council of Churches, and not the ANC as the government had claimed. Botha steadfastly refused to testify before the TRC.

By no means a complete record of apartheid’s wrongdoings, the perpetrators of other unsolved crimes, including murders and disappearances, were also revealed at the hearings.

Controversially, Tutu’s own son, Trevor, also appeared before the TRC. He had been arrested in 1989 at East London Airport for falsely claiming there had been a bomb on board a South African Airways airliner.

Convicted on contravening the Civil Aviation Act, he was sentenced to three-and-a-half years in prison. He announced his intention to appeal – but failed to attend his bail hearing and was finally arrested in August 1997. He applied for amnesty from the TRC which was granted later that year, a move that some decried as preferential treatment by a commission co-founded and chaired by his father.

Retirement

In 1997, Tutu was diagnosed with prostrate cancer. He underwent lengthy and successful therapy in Cape Town and New York but otherwise continued his TRC work. He was upbeat about his illness, telling Ebony magazine, “Yes, it would be nice to stick around a little longer. But I believe as a Christian that death is the end of one part, but the beginning of another. It’s like a doorway passing from one room of God’s wonderful world to another.”

Tutu retired as Archbishop of Cape Town in 1996 – whereupon he was promptly made emeritus Archbishop of Cape Town, an honorary title that is unusual in the Anglican Church. He continued to work as a global activist, on issues pertaining to democracy, freedom and human rights.

His friend, former President Nelson Mandela, went on to describe him as “sometimes strident, often tender, never afraid and seldom without humour, [his] voice will always be the voice of the voiceless”.

That voice was now however aimed squarely at the ANC as Tutu set about condemning the government for failing to deal with corruption, poverty and the xenophobic violence in the townships.

Invited to deliver the 2003 Nelson Mandela Foundation Lecture, Tutu used the occasion to attack the country’s political elite, pointing out that attempts to boost black economic empowerment were only benefiting an elite minority, while political “kowtowing” within the ANC was hampering democracy.

The remarks angered President Thabo Mbeki, who responded in his weekly online column:

“It would be good if those that present themselves as the greatest defenders of the poor should also demonstrate decent respect for the truth.”

“Thank you Mr President for telling me what you think of me,” Tutu replied. “That I am a liar with scant regard for the truth and a charlatan posing with his concern for the poor, the hungry, the oppressed and the voiceless. I will continue to pray for you and your government by name daily as I have done and as I did even for the apartheid government.”

Greater scorn was however reserved for Mbeki’s nemesis and eventual successor, Jacob Zuma.

In August 2006 Tutu urged Zuma to drop out of the ANC’s presidential succession race and warned, in a public lecture, that he would not be able to hold his “head high” if Zuma, a man who had been accused of both rape and corruption, was made leader. A month later, he again voiced his opposition to Zuma’s leadership bid due to his “moral failings”.

Later he would criticise the government over its refusal to issue a visa to the Dalai Lama, accusing Zuma’s administration of “kowtowing to China”.

By May 2013, Tutu had grown so disillusioned with the ruling party that he declared he was no longer able to vote for it. “The ANC was very good at leading us in the struggle to be free from oppression,” he said.

“But it doesn’t seem to me now that a freedom-fighting unit can easily make the transition to becoming a political party.”

Tutu did however attend the funeral. “I was quite astounded,” he later said. “I was very hurt. They have the right to say who would speak, but I think they shot themselves comprehensively in the foot in snubbing me. It was very sad.”

Tutu’s relationship with Mandela ran deep. He had introduced Mandela to the crowds on the Grand Parade in Cape Town in February 1990 when the ANC leader had made his first public appearance after his release from Victor Verster prison. Later, Mandela would spend his first night in freedom at Tutu’s official residence. Four years later, it was Tutu who had blessed Mandela at his inauguration as the country’s first democratically elected president.

Desmond Mpilo Tutu was born in Klerksdorp, in the then Transvaal, on October 7, 1931, the only son of Zacheriah and Aletta Tutu’s four children. When he was 12, the family moved to Roodepoort, outside Johannesburg, where his mother found work as a cook at the Ezenzeleni School for the Blind.

It is here, accompanying his mother to work, that the young Tutu met Trevor Huddleston, the Sophiatown priest. The encounter made a lasting impression on the boy.

“One day,” he recalled, “I was standing in the street with my mother when a white man in a priest’s clothing walked past. As he passed us he took off his hat to my mother. I couldn’t believe my eyes – a white man who greeted a black working class woman!”

No money to study medicine

Tutu had wanted to be a medical doctor – but his family couldn’t afford to send him to university. Instead, he chose to become a teacher, like his father, and studied at the Pretoria Bantu Normal College from 1951 to 1953, and went on to teach at Johannesburg Bantu High School and at Munsieville High School in Krugersdorp.

Tutu gave up teaching when the ravages of the Bantu Education Act became apparent and returned to studying, this time theology, at St Peter’s Theological College in Johannesburg.

He married Nomalizo Leah Shenxane, a teacher, on July 2, 1955. The couple went on to raise four children: Trevor Thamsanqa Tutu, Theresa Thandeka Tutu, Naomi Nontombi Tutu and Mpho Andrea Tutu. All were educated at the Waterford Kamhlaba School in Swaziland.

Tutu was ordained as an Anglican priest in December 1961 and travelled to King’s College, London, where he continued his studies and received his master’s in theology in 1966. During this time, he had also worked as a part-time curate.

He returned to South Africa in 1967 to take up the position of University of Fort Hare chaplain. From 1970 he lectured at the National University of Lesotho, but returned to the UK in 1972, where was appointed vice-director of the Theological Education Fund of the World Council of Churches. He returned to South Africa in 1975 and, taking up residence in Soweto’s famed Vilikazi Street, was appointed dean of St Mary’s Cathedral in Johannesburg.

Following the Soweto riots in 1976, Tutu became an increasingly vocal supporter of economic sanctions and a vigorous opponent of US president Ronald Reagan’s “constructive engagement” with the Nationalist government.

A brave man

In 1978, he was appointed general secretary of the SACC, a position he used to further rally support, both local and international, against apartheid. He was just as harsh in his criticism of the violent tactics later used by some anti-apartheid activists, and was unequivocal in his opposition to terrorism and communism.

Tutu was a remarkably brave man – and in July 1985 had famously intervened to rescue a suspected police informer from being burnt alive by an angry mob in Duduza township, on the East Rand.

In the democratic era, Tutu continued to champion the causes of the developing world, and has lent his support to human rights struggles in Palestine, China, Tibet and elsewhere, and lent his support to such diverse causes as the battles against climate change and poverty, and the campaigns for assisted dying, church reform and gay rights.

In 2003, he was elected to the board of directors of the International Criminal Court’s Trust Fund for Victims, and emerged as a staunch opponent of the war in Iraq, harshly criticising British prime minister Tony Blair for his support of the US-led invasion. In 2006 he joined the UN advisory panel on genocide prevention.

He had initially planned on entering a phased retirement from public life in October 2010, on his 79th birthday. “Instead of growing old gracefully,” he explained, “at home with my family – reading and writing and praying and thinking – too much of my time has been spent in airports and in hotels.”

Failing health

These plans, however, came to nothing and it was only his failing health that forced his eventual withdrawal from public life. He spent several weeks in hospital in September 2015, battling a persistent infection resulting from the prostate cancer treatment he had been receiving for nearly 20 years.

However, in the midst of his ailing health, Tutu and Leah made time to celebrate their anniversary 60 years after saying “I do”.

In his sermon, Reverend Canon Professor Barney Pityana described the young Tutu as “full of love” while he was still dating Leah.

“He was never shy to express it. He was so consumed by love for her that he would whisper sweet nothings in her ear and express his love in poetic terms,” he said.

Closer to the departure hall

The couple’s daughter Reverend Canon Mpho Tutu presided over the vows.

Almost a year later, Tutu was back in the hospital bed, nursing his infection. He was however released in time to celebrate his 85th birthday, which he spent presiding over Eucharist at St George’s Cathedral in Cape Town.

Tutu paid a moving tribute to the cathedral before laying his head on the communion table and weeping briefly.

“I have reached the stage in life when I am closer to the departure than arrivals hall. I have indicated that when the time comes I would like to rest here, permanently, with you,” he told the worshippers.

Before enjoying a cup of tea with the congregants after the service, he raised eyelids and ruffled a few feathers when he came out in support of assisted dying.

Tutu said he did not wish to be kept alive at all costs.

“I hope I am treated with compassion and allowed to pass on to the next phase of life’s journey in the manner of my choice.

“Today, I myself am even closer to the departures hall than arrivals, so to speak, and my thoughts turn to how I would like to be treated when the time comes. For those suffering unbearably and coming to the end of their lives, merely knowing that an assisted death is open to them can provide immeasurable comfort,” Tutu said.

Nobel Peace Prize

His statement garnered mixed reactions both inside religious circles and outside it, but he stuck to his guns as he had always done throughout his life.

In a rare sighting in March 2017, Tutu visited the home of former human rights lawyer Judge Essa Moosa, who succumbed to his cancer illness, and prayed with the family at their home in Belgravia.

Tutu has received several awards for his humanitarian work, as well as numerous doctorates and fellowships from universities around the world. In addition to the Nobel Peace Prize, which he received in October 1984, he was awarded the Albert Schweitzer Prize for Humanitarianism in 1986, the Pacem in Terris Award in 1987, the Sydney Peace Prize in 1999, the Gandhi Peace Prize in 2007, and the US Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2009.

He is survived by his wife, four children, seven grandchildren and great-grandchildren.