Opinion

Presidential Pardon: Letter to Bilyamin Bello

Forgive the intrusion of this letter. I know it is a strange thing to write to the dead, to address one who now sleeps beyond the reach of reply. I never knew you in life; I came to know you only through the news of your death, through the grief that trailed your name across our country’s conscience. Though this letter can never reach you where you rest, I write in the hope that it might serve as a small act of remembrance, a way of saying that you once lived among us, that your story still stirs the living, and that memory resists silence. That said, it was the German philosopher, Friedrich Nietzsche, who described birth, marriage, and death as the great crises of life; moments when existence reveals its deepest contradictions. In those three moments of arrival, union, and departure, life discloses its harshest paradoxes. Birth thrusts us into existence; marriage binds us to another in the covenant of intimacy; and death completes the circle, summoning us back into silence.

In each, we are both subject and spectator, trembling before the mystery of being. You, Bilyamin, did not know that your marital crisis would come not at the twilight of your days, but within the intimacy of love itself. When you stood before witnesses and sealed your life to Maryam Sanda, you were fulfilling life’s sacred promise: the human yearning to belong, to build a home, to continue the fragile chain of existence through children and companionships. In those early days, you were, by all accounts, joyful. The faces in your wedding photographs beam with quiet assurance. You were a man who believed in beginnings, in the hope that love, properly tended, could outlive the tempests of marriage. But the gods, ever unkind to those who trust too deeply in the permanence of things, had woven a different fate. Love, which once began in tenderness, slowly degenerated into resentment; the embrace that so often restores quarrelling hearts after a fragile truce became, for you both, the gesture of a final parting.

You and Maryam began as lovers, but ended as adversaries in a domestic tragedy that devoured you both. You died; she awaited the hangman’s noose, caught between remorse and retribution. The day you died, it was not only your body that was broken, it was the illusion that love alone can save us from ourselves. Your death, Bilyamin, was more than a crime; it was a rupture in the moral fabric of a country that has grown numb to horror. The news of your murder travelled across our country like an electric jolt. For a brief moment, we grieved, we remembered that violence is not a statistic but a face, a name, and a family left behind. The courtroom became the site of collective reckoning. Justice, often sluggish and uncertain, appeared to find its voice. Maryam Sanda was tried, convicted, and sentenced to death. The law spoke in your defence. Many watchers of her trial weren’t stunned. The conviction and sentence symbolised the moral weight of consequence. In that judgment, the state recognised that privilege and pedigree should not place one above the reach of justice.

Yet, years later, the very architecture of justice that dignified your memory began to crumble. The President, exercising his powers under Section 175 of the 1999 Constitution, extended clemency to Maryam Sanda. The act was cloaked in the language of compassion and justified as an expression of sovereign mercy. But, beneath it lay the troubling question: on whose behalf was this mercy granted? Mercy, Bilyamin, is a noble word. It speaks of redemption and the possibility that even the guilty may find grace. But in a country where justice is unevenly dispensed, mercy often arrives not as grace but as mockery, as I noted in this column last week. The President’s signature, solemn with the weight of executive grace and sanctified by the force of law, became an eraser of memory.

Yes, the Constitution gives the President vast discretion, but discretion without discernment is the enemy of justice. The power to pardon is not a personal indulgence; it is a solemn trust, meant to temper justice with mercy, with compassion, not to extinguish it. In ancient thoughts, from Aristotle to Aquinas, mercy was seen as the companion of justice, not its rival. Mercy does not abolish the moral order; it restores it by acknowledging remorse, repentance, and the possibility of moral renewal. What repentance had Maryam shown? The public was offered some jejune excuse, little more than a tale told by idiots, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.

Brother, your case exposes a deeper malaise in our collective conscience. We are a people who mourn briefly and forget swiftly. Our compassion is theatrical; our justice, performative. We parade our tragedies on social media, only to abandon them and move from outrage to forgiveness without passing through remembrance. In that restless cycle, pain is trivialised, and the dead are betrayed twice. First, by their killers; and later by our forgetting. Marriage, as Nietzsche saw it, is one of life’s great crises because it forces us to confront our own imperfections in the mirror of another. But marriage is also a performance of possession. Men and women enter it carrying the burden of ownership, jealousy, pride, and the fear of losing control. Your death stands at the intersection of these anxieties. Yet, such anxieties should never have led to death, but they did. In many homes where violence simmers and anger festers, truces are sealed with kisses and apologies. Yours, tragically, ended in death.

Unfortunately, the law that was supposed to stand guard over justice for you has now been weakened by the politics of sentiment. The President’s clemency, defended as an act of a constitutional sovereign grace, has now set a dangerous precedent: that the solemn verdict of a court, affirmed through due process, can be nullified by political will without cogent public explanation. It cheapens the sanctity of justice, turning it into a transaction of emotions rather than a discipline of law. The prerogative of mercy, as constitutional scholars remind us, exists not for the powerful but for the powerless, the remorseful, the wrongly convicted, and the forgotten souls on death row whose humanity has not yet been extinguished. It was never meant to rescue the privileged from consequence.

I would like to know what you would say, Bilyamin, if you could stand before us now. Would you speak of forgiveness? Would you ask, with the calm of the grave, if mercy is still divine? Perhaps, in your silence, there is an answer. Forgiveness is a sacred act, but it cannot be coerced by fiat. True forgiveness is born in the slow labour of remorse, in the acknowledgement of guilt, and in the willingness to bear the weight of one’s wrongdoings. Mercy imposed from above without the consent of justice becomes a form of injustice itself. Your story should remind us that law is not merely about punishment; it is about meaning. Every judgment handed down by a court is a statement about what a country refuses to tolerate. When mercy distorts justice, it fractures the moral continuity between the living and the dead. There is also something larger at stake: our country’s moral memory. Memory, according to Milan Kundera, is the guardian of identity. When states wield mercy without transparency, they invite the erosion of moral memory.

Dear Bilyamin, this letter is not only to you, it is also to us. It is a mirror held up to a country that has lost the capacity for moral astonishment. We live amid cruelty and call it culture; we pardon murder and call it mercy. We turn justice into a spectacle, then shrug when the lights go out. Beloved, you should have grown old. You should have watched your children walk, speak, and laugh. You should have argued about bills, worried about school fees, and aged gracefully. But time was stolen from you, and in granting mercy to your killer, the state robbed you again; this time of the justice that was meant to honour your absence. Yet, I write to you because memory resists erasure.

Nietzsche was right: life is a series of crises. Perhaps, he did not see that the greatest crisis is not birth, or marriage, or death, it is forgetting. For to forget is to die twice. Forgetting means allowing injustice to flourish without consequence. Rest now, Bilyamin. The rest of us will continue to wrestle with the meaning of your death, with the haunting question of whether mercy can ever be just when it mocks the memory of those who can no longer speak. If your silence could become language, it might tell us this: that love must never kill, and justice must never forget to answer to itself.

Sleep well, native of my person.

Abdul Mahmud is a human rights attorney in Abuja

-

Politics17 hours ago

Politics17 hours ago2027: Real-time results transmission achievable, say telcos

-

Business21 hours ago

Business21 hours agoNUPENG asks Tinubu to clarify new executive order on oil and gas industry

-

News22 hours ago

News22 hours agoMonthly environmental sanitation yet to resume – Lagos

-

Business22 hours ago

Business22 hours agoDangote Refinery targets depot owners, major marketers in new marketing model

-

News21 hours ago

News21 hours agoActivist kicks as Plateau sponsors pilgrims with N7.48b

-

World News22 hours ago

World News22 hours agoViolence erupts across Mexico as army kills drug cartel leader

-

World News21 hours ago

World News21 hours agoUS Secret Service kills man trying to break into Trump estate

-

News22 hours ago

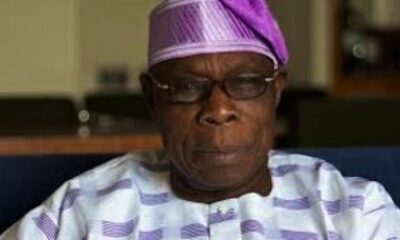

News22 hours ago89th birthday: Obasanjo targets 10,000 Lagos residents for free healthcare