Opinion

2027 Polls: The INEC chairman Nigeria needs

The Chairman of the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC), Mahmood Yakubu, will bow out of office in November, having completed his record two-term tenure of 10 years. His successor, ideally, is expected to assume office immediately, as the position abhors a vacuum.

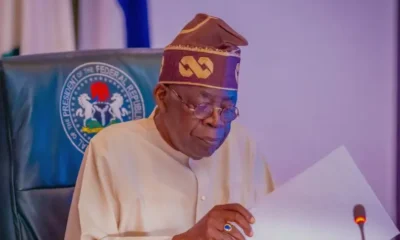

Who that successor would be is a matter of deep public interest, given the series of integrity questions that have trailed Nigeria’s electoral processes and outcomes since 1999. President Bola Ahmed Tinubu alone is vested with the power to choose Mr Yakubu’s replacement, in line with Section 154 (1) and (2) of the 1999 Constitution, as amended, which requires him to “consult with the Council of State” in making the appointment.

With the president’s personal interest in re-election in 2027, and with the premature buildup to it already reaching a near frenzy, his choice of INEC chairman will attract an unusual level of scrutiny. The position, like those of the supporting electoral commissioners, is not open to partisans or card-carrying members of any registered political party. It is a role designed strictly for individuals whose fidelity must be to the Constitution and, by implication, the Federal Republic of Nigeria.

The search for a new national electoral umpire should begin now to avoid the sort of delay created by former President Muhammadu Buhari in appointing Attahiru Jega’s successor. Mahmoud Yakubu’s appointment came on 21 October 2015, even though his predecessor had left office on 30 June that year.

The interim successor arrangement had itself sparked controversy. Mr Buhari’s decision to appoint Amina Bala Zakari, a day after Mr Jega, a professor, handed over to Ahmed Wakil, as acting INEC chairman, was hotly contested. It was true that Mrs Zakari, being the most senior National Electoral Commissioner after the exit of Mr Wakil, was next in line, but her appointment ignited claims of a filial relationship with the president.

Nigerians and election observers across the world, therefore, have sufficient grounds to be deeply concerned about the character and antecedents of whoever becomes the next INEC boss. Sadly, since 1999, a number of INEC chairmen have been perceived as beholden to the regimes that appointed them or to the ruling party, thereby raising questions about their independence and impartiality. This perception was most glaring in the brazen bias exhibited during the 2007 general elections, which were underpinned by the “do-or-die” mentality of the ruling regime at the time.

During that presidential election, the INEC chairman, Professor Maurice Iwu, reportedly excused himself from the collation of results at the commission’s headquarters, leaving party agents behind. Results were subsequently announced, declaring “…the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP) candidate (as) winner on the basis of results electronically transmitted…from 13 states, while the results from 23 states were still being awaited,” as documented in Professor Ben Nwabueze’s 2009 book, Judicialism and Good Governance in Africa.

In addition, ballot papers in that election had no serial numbers, and the breakdown of votes scored by each presidential candidate in all the states was not made public. It was little surprise that its ultimate beneficiary, the late President Umaru Musa Yar’Adua, admitted that the election that brought him to power was flawed. Consequently, he set up the Mohammed Uwais Electoral Reforms Committee to forestall such travesties in future elections. The perverted and judicially contested outcomes of off-cycle gubernatorial polls in Anambra, Bayelsa, Edo, Ekiti, Osun, and Kogi states stood as further testament to the abysmal performance of INEC’s leadership between 2003 and 2007.

Attahiru Jega tried to improve the system. Yet the toxicity of electoral administration in Nigeria persisted. To restore public confidence, Mahmood Yakubu introduced several reforms before the 2023 elections “to avoid the usual challenges,” as he put it. These included, among others, electronic transmission of results from polling units to collation centres and the IRev portal for public viewing of results.

Rather incredibly, of the three national elections — the Senate, the House of Representatives, and the Presidency — conducted simultaneously with the same voters, only the presidential results suffered delay in display on the iRev portal, unlike the other two. INEC attributed this failure to a “technical glitch.” Unsurprisingly, suspicions and allegations of manipulation were rife.

Glaring inconsistencies in the outcomes of the 2023 general elections reportedly remain visible on INEC’s website. Media organisations such as PREMIUM TIMES and the BBC, alongside civil society group Yiaga Africa, separately reported — based on figures from the INEC portal — that Peter Obi, not Bola Tinubu, won the presidential election in some parts of Rivers State, contrary to the official declaration. This remains a searing indictment of electoral integrity in Nigeria.

The well-considered opinion of Justice George Oguntade of the Supreme Court, though expressed as a minority position, remains instructive. He argued that “…at the conclusion of an election, an unbiased observer should be able to see that the election was free, fair, transparent and that no room had been left open for malpractices to occur.” This should serve as the guardrail for the conduct of the 2027 polls.

But there are growing reservations that this may be wishful thinking, given some troubling developments already emerging within INEC. The Socio-Economic Rights and Accountability Project (SERAP) has accused President Tinubu of appointing at least three partisan individuals as National and State Resident Electoral Commissioners.

This, among other concerns, should not be dismissed. Still, the president has an opportunity to go beyond the bare prescriptions of the 1999 Constitution and adopt global best practices in selecting Mr Yakubu’s successor. Many countries employ broader, more consensual methods for appointing the heads of their election management bodies.

In South Africa, candidates are chosen from a pool recommended by multi-party parliamentary panels, with opposition parties playing a crucial role in the vetting process. In Ghana, opposition parties are consulted before the national electoral umpire is appointed. By contrast, in Nigeria, the Council of State merely listens to the president’s presentation of his choice without meaningful input.

Where electoral commissions have multi-party representation — as in the United States, which includes three members from each major party — credibility is infused into the process, suspicion of ruling party domination is reduced, and trust in the electoral system is enhanced. We recommend this inclusivity going forward, as a necessary step to wean INEC of its current shadowy and manipulative image.

•Editorial By Premium Times

-

News2 hours ago

News2 hours agoFG makes U-turn, says Maths compulsory for Arts students

-

Business2 hours ago

Business2 hours agoFCMB Partners NCDMB, BoI to Disburse ₦15 Billion Loan to Local Contractors in the Oil and Gas Sector

-

Politics2 hours ago

Politics2 hours agoTinubu Is An Angel Sent By God To Fix Nigeria – Yahaya Bello

-

News2 hours ago

News2 hours agoAlleged Coup Plot: Ex-governor Under Watch

-

News2 hours ago

News2 hours agoAiling Finance Minister Back In Nigeria After UK Medical Trip

-

Sports2 hours ago

Sports2 hours agoEPL: Man United beat Liverpool at Anfield — first win since 2016

-

Business2 hours ago

Business2 hours agoTinubu’s Presidential Pardon Can Damage Investors’ Confidence – CPPE

-

Business2 hours ago

Business2 hours ago$42.37 Billion Under-Remittance: FG Extends NNPCL Probe To December 2024