Business

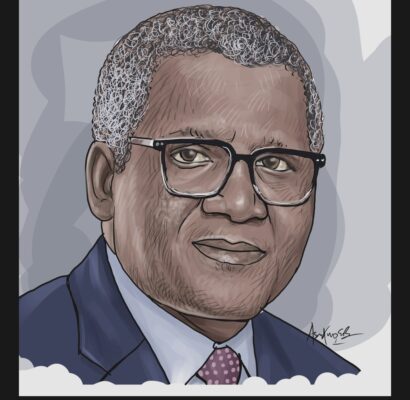

BusinessDay’s Man of the year: How Africa’s richest man bet everything on a refinery & won

When Aliko Dangote first announced his intention to build a private oil refinery in Nigeria back in 2013, skeptics outnumbered believers.

At a business luncheon that year, one media executive from a major Nigerian newspaper declared that the country’s environment was unsuitable for such an ambitious venture. “Only a foolish man will build a refinery in Nigeria,” he remarked.

Dangote, listening intently, interjected with characteristic boldness: “I am that foolish man.”

Twelve years later, that ‘foolish’ decision has transformed Nigeria’s economy, stabilised its currency, and positioned Dangote as not merely a businessman but a nation-builder. For steering Africa’s largest economy through its most significant industrial transformation in decades, Aliko Dangote is BusinessDay’s 2025 Man of the Year.

The genesis

The roots of the Dangote Refinery project trace back to 2007, when the billionaire industrialist led a consortium that purchased two of Nigeria’s moribund state-owned refineries, Port Harcourt and Kaduna, for approximately $670m.

But the incoming Umaru Musa Yar’Adua administration, pressured by labour unions arguing the ‘national patrimony’ had been undervalued, reversed the sale.

Dangote walked away bruised but unbowed. The setback crystallised a more radical vision: rather than rehabilitate decrepit infrastructure, he would build the largest single-train refinery in the world from scratch.

Six years after that humiliation, in September 2013, he unveiled plans for a $9bn private refinery with a capacity of 650,000 barrels per day, exceeding the combined capacity of Nigeria’s four existing refineries. The project would eventually balloon to $19bn, then $20bn, testing even Dangote’s legendary risk appetite.

“It was the biggest risk of my life,” Dangote told Forbes earlier this year. “If this didn’t work, I was dead.”

The audacity of the venture cannot be overstated. Nigeria, despite being Africa’s largest oil producer, had spent 28 years importing virtually all its refined petroleum products.

Successive governments had poured $25 billion into failed attempts to revive state-owned refineries, which operated far below capacity when they functioned at all. The country’s downstream oil sector had become a byword for dysfunction, riddled with opaque swap deals, inflated import contracts, and endemic corruption.

Refinery’s strength

Construction began in earnest in 2017 at the Lekki Free Trade Zone outside Lagos, on a site spanning 6,180 acres, equivalent to nearly 4,000 football pitches. What emerged over the following years was a petrochemical complex of staggering ambition.

The refinery boasts a Nelson complexity index of 10.5, making it more sophisticated than most American refineries (average 9.5) or European facilities (average 6.5). In 2019, the world’s largest crude distillation column, weighing 2,350 tonnes and standing 112 metres tall, taller than the Saturn V rocket, was installed. That same year, three more world records were set with the installation of the world’s heaviest refinery regenerator at 3,000 tonnes.

The facility generates its own 435-megawatt power supply and features dedicated marine facilities with single-point moorings capable of handling ultra-large crude carriers.

When President Muhammadu Buhari officially inaugurated the refinery on May 22, 2023, it stood as the largest private-sector investment in African history. Yet, operational challenges remained. The refinery began producing diesel and aviation fuel in January 2024, but ramping up to full gasoline production proved arduous.

A vision that stunned observers

Pat Utomi, a professor and political economist and pioneer teacher of entrepreneurship at Lagos Business School, had believed in Dangote’s potential for decades. Nearly two decades ago, he wrote an op-ed suggesting Nigeria could claim its promise if it found 200 entrepreneurs like Aliko. When they met at the airport the day that piece appeared, they discussed the vision. But even Utomi wasn’t fully prepared for what he would witness years later.

When a friend visiting from New York requested a tour of the Dangote refinery as part of his Nigerian tourism experience, Utomi reluctantly agreed to accompany him. What he saw left him gasping.

“The visit to Ibeju Lekki left me stunned and gasping for breath,” Utomi recalled. “The audacity of the vision and the stunning courage for commitment bordering on positive recklessness, where Eagles dare, could be seen on display any which way you looked.”

The scale was unprecedented. “A production facility several times the size of Victoria Island is audacious anywhere, any day,” Utomi observed. But it wasn’t just the physical magnitude that impressed him. It was the deeper context of what Dangote had overcome.

After the visit, Utomi revised his earlier assessment. “I felt like recalling my class and telling them I believed from seeing cement. Now that I have seen what I could not have imagined, I want to step up many notches in my position in the conversation,” he said. “After visiting the refinery, I have become convinced that ten Alikos could do for starters. Two hundred Alikos would be super great, but just ten would turn the fortunes of the continent around.”

Battling the oil mafia

Dangote’s greatest challenge wasn’t technical; it was political. The refinery represented an existential threat to what he candidly described as Nigeria’s ‘oil mafia,’ a shadowy network of politicians, traders, and businesspeople who had profited handsomely from the country’s dysfunctional oil sector for decades.

“I knew there would be a fight,” Dangote admitted at an investment conference in June 2024, “but I didn’t expect the oil mafia to be stronger than the drug mafia.”

Utomi watched this battle unfold with dismay. “Every time I hear NNPC people say something unsavoury about the Dangote refinery and their products, I shudder at the shamelessness of public officials in Nigeria,” he said bluntly.

“In normal countries the public officials would defend and promote such a venture with a passion reserved for safeguarding the family silver, but here it is NNPC people who have almost bankrupted the Treasury ‘repairing’ refineries I have repeatedly said are broken beyond mendable elastic limits and kept refinery staff on salaries doing nothing that are running down a $20bn investment in their own country. Who does that?”

The attacks from NNPC officials particularly galled Utomi. “They attack product quality, yet Dangote is exporting into the US market, which is the most quality-sensitive market that I know. Those who are the ultimate champions of monopoly are now accusing Dangote of monopoly intentions. This is beyond a lack of patriotism.”

He pointed to successful models elsewhere. “They should go and study how the old Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI) worked with Japanese companies in the 1960s and created the idea of Japan Inc. It was not just the Keiretsu that got support from the government, but the chaebols did in South Korea.”

Impact on Nigeria’s economy

By mid-2024, the Dangote Refinery was processing over 500,000 barrels per day and steadily ramping toward its 650,000-barrel capacity. In October 2025, Dangote announced plans to expand capacity to 1.4m barrels per day, which would make it the world’s largest refinery.

The economic impact has been profound and multifaceted. According to research by Analysts Data Services and Resources Limited, the refinery is projected to boost Nigeria’s GDP growth from 3.34 percent without the facility to 6.21 percent by 2030, adding over $400bn to the economy during that period.

Between June and July 2025, the refinery exported 1m tonnes of premium motor spirit to international markets, transforming Nigeria from a net importer to a net exporter of refined petroleum products for the first time in nearly three decades. The facility now ships products to Europe, Brazil, the United Kingdom, the United States, Singapore, and South Korea.

Impact on currency

Perhaps the most macroeconomic impact has been on Nigeria’s beleaguered currency. The naira, which had depreciated 41 percent in 2024, stabilised in 2025 as the Dangote Refinery reduced dollar demand for petroleum imports.

Nigeria previously spent 40 percent of its foreign exchange earnings importing refined products. With local production meeting most domestic demand, pressure on forex reserves eased substantially. Findings by BusinessDay showed the country saved an estimated $20bn in fuel import costs in 2025 alone.

The naira has shown remarkable resilience despite global headwinds. After hitting lows of N1,675 per dollar in November 2024, the currency strengthened to approximately N1,450 per dollar by December 2025, an appreciation of roughly 13 percent. External reserves grew to $44.56bn, providing the Central Bank of Nigeria with leverage to defend the currency.

The currency stability has had cascading effects on inflation. Food inflation, driven partly by import costs, declined from 34 percent year-on-year in April 2024 to below 22 percent by mid-2025. Headline inflation fell to 14.45 percent, aligning with the president’s projected figure of 15 percent at the end of the 2025 and budget projected target.

Challenges and Controversies

The path forward is not without obstacles. In March 2025, a dispute erupted when the refinery temporarily suspended naira-based sales, citing a mismatch between its local currency proceeds and dollar-denominated crude oil obligations. The move triggered petrol hoarding and price speculation, highlighting the fragility of supply arrangements.

Federal officials scrambled to salvage the naira-for-crude arrangement, with a technical subcommittee reconvening to review terms. The incident underscored ongoing tensions between the refinery, the NNPC, and international oil companies accustomed to exporting crude rather than supplying domestic refiners.

In September 2025, the refinery dismissed 800 employees accused of sabotage, triggering a protest strike by the Petroleum and Natural Gas Senior Staff Association of Nigeria. The episode revealed internal pressures as the facility scales operations.

Environmental activists have also questioned the wisdom of building a massive fossil fuel refinery in an era of climate transition. Dangote Group has responded by emphasising its commitment to producing Euro-V quality fuels that meet European environmental standards, positioning the facility as producing “efficient and clean fuels.”

Yet for Nigeria and much of Africa, where energy resources remain underutilised and per capita emissions are among the world’s lowest, the calculus differs from developed nations. As Devakumar Edwin, the group’s executive director for strategy, explained: “Nigeria exports raw materials and imports finished products. When you import the finished product back, you are essentially importing poverty into the country.”

Addressing critics with evidence

Utomi addressed the criticisms head-on in his Executive MBA class, using the Dangote case as a teaching opportunity. He asked students to examine the complaints against Dangote, from allegations of government waivers to claims of unfair advantages.

“Whether these be true, exaggerated or contrived was not key to the exercise,” Utomi explained. He then challenged the class to compare Dangote with other business leaders who had received equal or greater government favour in decades past.

“The question that followed was how many of the equally favoured or better advantaged have had an impact of his scale in creating jobs, contributing tax flows and propelling a prosperity paradox, as Clayton Christensen would call the art of creating new markets and erecting value chains where none existed.”

The lesson was clear. “Show me Mai Deribe’s garage of dozens of decaying status cars with his influence and access to the powerful in those days,” Utomi told the class, “and I will show you why Aliko deserves to be seen as a national treasure.”

Utomi found the class’s response compelling, but his conviction deepened after visiting the refinery himself. “I am glad my friends who invited me to visit the Eloko Beach Refinery for the privilege to witness so many Nigerians creating value in concert did. This is what the country needs. I am pleased to celebrate Aliko Dangote for doing this.”

A national treasure vindicated

At 68, an age when many industrialists contemplate succession and legacy, Dangote is planning refinery expansion, new listings, and continental market integration. His vision extends beyond Nigeria to the African Continental Free Trade Area, where his cement, fertiliser, and petroleum products could serve 1.3bn people across 54 countries.

The “foolish man” who announced his refinery plans in 2013 has been vindicated. His facility has stabilised Nigeria’s currency, slashed import bills, created jobs, attracted investment, and repositioned the country as a net exporter of refined products. These are accomplishments that eluded governments for three decades.

For conceiving and executing a project that has fundamentally altered Nigeria’s economic trajectory, for demonstrating that African capital can drive African development, and for providing a blueprint for industrialisation that the continent can follow, Aliko Dangote is BusinessDay’s 2025 Man of the Year.

(BusinessDay)

-

News3 hours ago

News3 hours agoDIG Mba, others retire, seven AIGs for promotion

-

News3 hours ago

News3 hours agoDetention: El-Rufai Petitions ICPC, Demands N15.6bn Damages

-

News3 hours ago

News3 hours agoBorno: Hundreds still missing after Boko Haram attack

-

World News22 hours ago

World News22 hours agoHow Iran Strikes Have Damaged US Military Sites – CNN

-

Politics3 hours ago

Politics3 hours agoTinubu Elevates Masari To Special Adviser

-

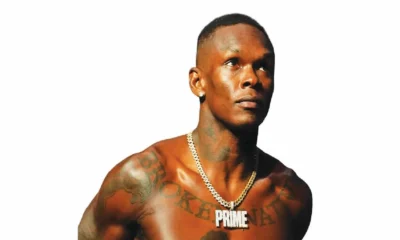

Sports3 hours ago

Sports3 hours agoAdesanya demands $15m per fight from UFC boss White

-

Politics4 hours ago

Politics4 hours agoWe Will Adopt Tinubu As 2027 Presidential Candidate – APGA

-

Business3 hours ago

Business3 hours agoMiddle East Crisis: We’ll Ensure There Is No Fuel Scarcity In Nigeria, Says Dangote Refinery