Democrats Decide That Joe Biden, as Risky as He Ever Was, Is the Safest Bet

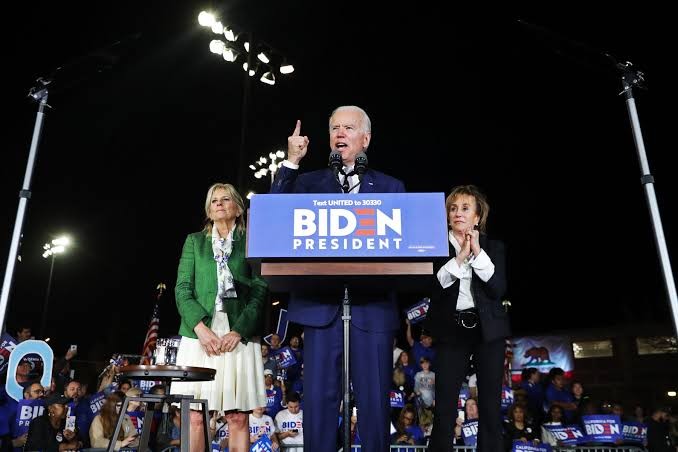

“They don’t call it Super Tuesday for nothing!” he told supporters in Los Angeles, shouting through a list of states he had won amid a medley of fist-pumps and we-did-its.

But a week ago, the result would have been something close to unthinkable.

Lifted by a hasty unity among center-left Democrats disinclined toward political revolution, Mr. Biden has propelled himself in the span of three days from electoral failure to would-be juggernaut. He has demonstrated durable strength with African-Americans and emerged as the if-everyone-says-so vessel for tactical voters who think little of Senator Bernie Sanders and fear that his nomination would mean four more years of President Trump.

Mr. Biden’s performance included decisive early wins across the South, victory in delegate-rich Texas and triumphs in some places where he did not even campaign as Super Tuesday approached, like Minnesota and Massachusetts, home to Senator Elizabeth Warren. The dominant showing made clear that the primary has effectively narrowed to a two-man race with Mr. Sanders, as Michael R. Bloomberg’s first brush with national voters yielded meager returns on a colossal financial investment.

For all Mr. Biden’s stumbles — in Iowa, in New Hampshire, at debates, at his own events — perhaps all voters needed was to hear him give a victory speech.

That happened on Saturday, in South Carolina, where Mr. Biden seemed to temporarily erase every latent concern that had accumulated for nearly a year about his bid.

Yet any suggestion that Mr. Biden is now a risk-free option would appear to contradict the available evidence.

He is no safer with a microphone, no likelier to complete a thought without exaggeration or bewildering detour.

In fact, Mr. Biden has blundered this chance before — the establishment front-runner; the last, best hope for moderates — fumbling his initial 2020 advantages in a hail of disappointing fund-raising, feeble campaign organization and staggering underperformance.

When it mattered most, though, the judgment came swiftly from Sanders-averse Democrats.

All right, we’ll take him.

The consequence — after a yearlong winnowing from a field that once included many women, nonwhite candidates and up-and-coming political talents — is that Democrats are very likely to nominate one of two septuagenarian white men with conspicuous political baggage. Any safety in that choice is relative.

“John Kerry, Al Gore and Hillary Clinton,” said Rebecca Kirszner Katz, a veteran progressive strategist. “All safe choices.”

Two different coalitions emerged in support of two very different candidates, turning the Democratic race into a two-person contest between Joe Biden and Bernie Sanders.

Voters wary of Mr. Sanders are probably right that supporting Mr. Biden is the tidiest way to keep the democratic socialist from the top of the ticket. They may yet be right that Mr. Biden would pose the strongest challenge to Mr. Trump. The former vice president is widely admired in the party for moving gracefully through tragedy and serving alongside Barack Obama.

But what if Mr. Trump is wrong? What if every elected official hustling to endorse Mr. Biden, after long resisting, is wrong, too? Recent election history, especially Mr. Trump’s, has been unkind to conventional wisdom.

Only a couple of weeks ago, some Biden allies were talking quietly about how he could, at least, end his campaign with dignity: Hang on narrowly in South Carolina, hopefully, and bow out, statesmanlike, if Super Tuesday went sideways as many expected.

That Mr. Biden’s fortunes have changed says more about the context of this primary than the content of his campaign. Current and former competitors, including Ms. Warren, former Mayor Pete Buttigieg and Senator Amy Klobuchar, all strained to connect with black and Latino voters. Mr. Bloomberg flailed on the debate stage as he stepped out from behind the reputational curtain of his ubiquitous advertisements. And many in the party have remained uncomfortable with the kind of unswerving progressivism that Mr. Sanders demands.

The depth of this last concern with Mr. Sanders is uncertain. Entering Tuesday, his predictions of runaway progressive turnout to his cause, a central premise of his case for his own electability, had not necessarily come to pass.

It is also quite possible, after all the Tuesday states are accounted for, that the delegate picture will look very competitive, particularly as full tallies from California roll in. Mr. Sanders remains popular across much of the party, even among many who did not consider him their first choice.

If nothing else, a Biden-Sanders matchup is the logical venue for the party’s foremost ideological debate about the proper scope and ambition of government — about whether Mr. Trump is a symptom of longstanding national ills or an “anomaly,” as Mr. Biden has suggested, whose removal should be the party’s chief animating priority.

“Sanders has more confidence that the voters are ready for big change,” said Barney Frank, the former Massachusetts congressman. “Biden, particularly after the eight years with Obama, has more of a sense that more government can be a hard sell.”

Mr. Frank said the race boiled down to this question: “Is the electorate more afraid of government than they are of inequality?”

The two contenders were products of the same era, shaped by very different forces within it. Mr. Sanders became a mission-driven lefty, enthralled by socialist and communist governments abroad and the fight for working people at home. Mr. Biden preferred a within-the-system approach, winning a Senate election at 29 and acknowledging some distance from the activist instincts of many contemporaries.

“I wore sport coats,” Mr. Biden told reporters once, explaining his limited involvement in antiwar zeal. “I was not part of that.”

That comment came as Mr. Biden sought the 1988 Democratic presidential nomination. Mr. Sanders ran for Congress that year. They both fell short. They both tried again.

For more than two decades, they served in the same Washington, amassing voting records that have often dogged them since. Mr. Sanders has said he regrets his voting history on some gun legislation; Mr. Biden has faced consistent criticism, including from Mr. Sanders, for his vote authorizing the use of military force in Iraq, among other decisions.

This paper trail convinced some 2020 strategists that both candidates would be vulnerable. Their own campaigns did not necessarily see it that way.

“I always thought that this race would be between the clash of two titans, of Bernie and Biden,” said Ro Khanna, a California congressman and Sanders campaign co-chair. “It’s odd that it wasn’t the conventional wisdom.”

Over the past year, alternative outcomes were easy to imagine. There were candidates of virtually every profile, including a half-dozen alone from Super Tuesday states, and a procession of fresh faces like Senator Kamala Harris and former Representative Beto O’Rourke who seemed primed to capitalize on voters’ curiosity.

Mr. Sanders was often dismissed as a factional candidate and 2016 retread even before he had a heart attack last fall.

Mr. Biden was depicted as a lackluster contender out of step with the times.

“You cannot go back to the end of the Obama administration and think that that’s good enough,” Mr. O’Rourke said last June, calling Mr. Biden a return to the past.

“I just think Biden is declining,” Tim Ryan, an Ohio congressman who was then running for president, said last September. “I don’t think he has the energy. You see it almost daily.”

Both men have now endorsed Mr. Biden’s campaign. Other fallen rivals, like Mr. Buttigieg and Ms. Klobuchar, have done the same.

Mr. Sanders has a theory about all that. “There is a massive effort trying to stop Bernie Sanders. That’s not a secret to anybody in this room,” he told reporters on Monday. “So why would I be surprised that establishment politicians are coming together?”

Of course, politics is about options, and Democrats suddenly have very few, even as some remaining candidates suggest they are being overlooked.

Both Ms. Warren and Mr. Bloomberg have effectively admitted that their only path to the nomination is a contested convention this summer. This has not stopped either from pressing on so far.

In California on Monday, Ms. Warren said that “no matter how many Washington insiders tell you” to support Mr. Biden, “nominating their fellow Washington insider will not meet this moment.”

Mr. Bloomberg, growing weary on Tuesday of questions about whether his run was aiding Mr. Sanders, framed the issue in reverse: “Why don’t they coalesce around me?” he asked of moderates during a stop in Florida.

By evening’s end, he seemed to have his answer. They had settled on someone else. (The New York Times)