Fallacy of so-called competence over zoning

I was once invited to the African Centre in London to give a talk on the concept of rotational presidency in Nigeria. It was a well-advertised lecture, so quite a number of Nigerians were aware of it. I did my best and got a standing ovation from the informed audience. However, an unpalatable incident occurred soon after the talk, as a compatriot from one of the northern states sought to engage me in a physical combat. It was the intervention of a Ghanaian friend that saved the day.

I am a Nigerian patriot, not one that would engage in ethnic profiling. I must, however, say that opposition to the idea of rotating the presidency has been rather opportunistic. Those who say the election or selection of the president should be based on competence only hide under the assumption of perceived regional advantage in population. If one must be brutally honest, it is in the comparatively more educated South, not the North, that an argument of so-called competence should be rending the air. We do not have a national population of voters that can take an objective look at a competition and side against ethnic or religious interests. Were the next two or three presidents to come from a regional grouping, there will not be a few who will be moaning and groaning about an hegemonic situation.

The major feuds in the Nigerian polity since independence in 1960 have been mainly over leadership. Be it the Civil War of 1967-70, or the Gideon Orkar-led attempted coup of April 1990, or the crisis we now simply refer to as “June 12”, it has been demonstrated in the course of our existence as an independent nation that the leadership question is indeed one question we cannot take for granted.

To the credit of Nigerians, the enormity of the leadership question appears to have been appreciated. The arrangement by the Peoples Democratic Party to rotate the presidency between the South and North is an acknowledgement of the existence of a most disturbing national problem and an effort to provide a practical solution to it. The PDP approach would appear to have reasonably stabilised Nigerian democracy in the last 20 years, and the fear of “ethnic hegemony” would appear not to have been as pronounced as it once was. Any scholar wanting to write on the relative stability of our democracy from 1999 to date must appreciate the fact of an informal rotation of leadership between the South and North as a factor.

However, we do not have “rotational presidency” yet. The principle has yet to be accommodated in the national constitution where its “nitty gritty” can be spelt out. Nevertheless, the significance of rotating the presidency can hardly be underestimated. The PDP has yet to recover from the backlash it suffered when it reneged on its important arrangement in the prelude to the 2015 presidential election. One reason the party lost that election was the withdrawal of support from the North whose voters had felt the presidential candidacy of the party should have come from their region.

A constitutional or political arrangement must accommodate the emotions and sentiments of those it is designed to serve if its usefulness is to survive the test of time. One has said it before and one is repeating it here, that the success of the American constitution is the acknowledgement by America’s founding fathers that the problem of cleavage can only be resolved by addressing it.

Their pragmatic decision to introduce a bicameral legislature was one “scientific” approach to addressing the fears of smaller states about the dominance of larger ones. Hence, the American states, irrespective of their sizes and populations, were accorded equal representation in the Senate. Today, no American state expresses the fear of being dominated by another. Nigerians who make uninformed comparisons between their nation and America, the fact that the North of the latter had produced more presidents than its South, need to be told that American regions are not divided along cultural or ethnic lines. One reason why the American democratic system prioritises the Electoral College vote over the popular vote in its presidential elections, is to protect the interests of smaller states from the overbearing influences of the larger ones.

Cleavages, be they those of ethnicity and religion, do not disappear by wishing them away. The sad prediction here is that our cleavages may eventually destroy our aspiration of one Nigerian nation if we do not learn how to manage them effectively. We sadly do not appear to want to be innovative. We chop for solutions that have been applied to the problems of other nations, while lacking the courage or patience to innovate homegrown solutions.

Critics of rotational presidency talk of having the “best candidate” for the job, even when they know that such a so-called best candidate always comes from a dominant regional grouping. There are “best candidates” in every region of the Nigerian federation, seeking an opportunity to bring their leadership qualities to bear on all of us. A nation can design a democratic structure that accommodates its realities. There is no universal structure of democracy, what is universal about democracy are the basic principles that govern it. The way the Americans elect their President is not the same way the British elect or select their Prime Minister. Rotational presidency is the appropriate leadership structure for Nigeria. I have been saying this for almost 40 years.

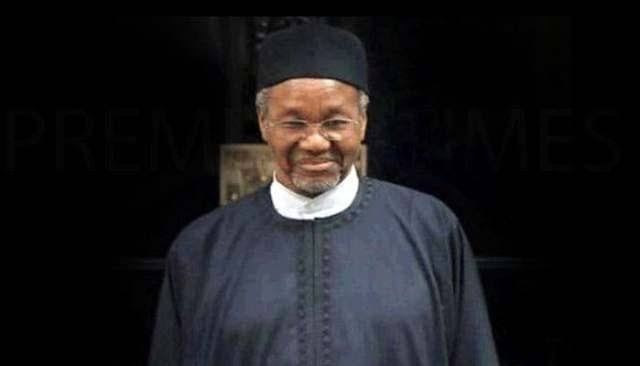

I submitted a detailed memorandum of this subject to the Political Bureau instituted by the government of General Ibrahim Babangida (retd) in 1986. Interestingly, a committee of intelligent, experienced and well-meaning Nigerians— The Patriots — articulated a similar proposal in 2000. The fact that we have ever since remained loyal to our viewpoint suggests honesty and conviction on our part.

We sadly have too many so-called opinion leaders in our society who say one thing today and another tomorrow. Sadly, because these so-called opinion leaders have been “former this” or “former that”, they get the attention they hardly deserve. Some pretend to be speaking for all of us, even when what they seek to protect is their own selfish or group interests. Rotational presidency, in this writer’s view, complements and enhances the principle of federalism. It will ensure the stability of an otherwise fragile nation.

•Dr Anthony Akinola is a scholar based in Oxford, United Kingdom