Is Nigeria’s official fuel pump price still official?

To reduce this huge financial (or fiscal) burden, Nigeria’s government in January 2012 attempted to free up the gasoline price by ending the subsidy regime and allowing demand and supply to determine the price. (The subsidy programme was also considered rife with double-dealing—about US$6 billion in fraudulent claims were made in 2012.) Although praised by the IMF, the move was met with a storm of protests at home, forcing the government to rescind its decision. Within two weeks, the price reverted from 141 naira to 97 naira per litre.

The fiscal dent (or ‘under–recovery’) of this, according to estimates by the NNPC, is US$2.3 million daily. This is a benefit that goes to the sellers and consumers of the products in the neighbouring countries rather than the consumers in Nigeria. This often creates scarcity, which drives up the black-market premium (BMP)—the difference between the unofficial (true) price and the official price.

It should be noted that if the BMP is zero, then there is perfect compliance by the distributors/retailers of the product: they are selling at exactly the official price. If, on the other hand, the BMP is greater than zero, then there is some non-compliance. Therefore the closer the BMP is to zero, the higher the level of compliance with the official price.

If the distance from the refinery (Nigeria has four functional refineries, although not operating at full capacity at the moment) and the cost of transporting the product significantly determines the variations, then the graph will be a straight 45-degree line and all the dots (or the state labels) will cluster around the line.

But what we see is partially the opposite: states that are closer to their nearest refineries tend to pay higher prices than other states. For example, Abia State is closer to its closest refinery (Warri refinery, Ekpan in Delta State) and still pays the highest pump price.

The correlation between the pump price and distance is negative at 11 per cent. The farther the state is from the refinery, the lower the pump price it pays, at least relative to other states.

On the graph, Delta, Kaduna and Rivers (the locations of three refineries) appear in the same area. The reason is simple: the distance from Delta to Delta is zero; the distance from Kaduna to Kaduna is also zero and so on.

But then, about 80 per cent of Nigerian petrol is imported. In this case, how is this brought into the country/distributed across the states? Answering these questions may shed some light on unravelling the source of variations.

The undersupply of gasoline has been the main justification for the fuel subsidy, and consequently the official pricing of the product. And as noted by Moss et al., “This has discouraged investment in domestic refining capacity. Of the 20 refinery licences issued since 2000, none have been used because the current market structure does not allow investors to fully cover their operational costs.”

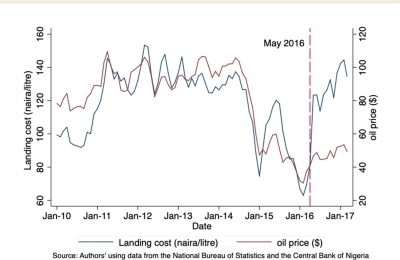

Since Nigeria imports over 80% of its petroleum products, local pump prices must be divorced from changes in international oil prices if they are to be kept stable. One way to do this is for the country to refine its fuel needs locally. This brings to the fore the forthcoming Dangote refinery, which is expected to be the largest in the world. If it succeeds, it will play a key role in revamping Africa’s largest economy. It will raise Nigeria’s external reserves by replacing imports of refined petroleum products that cost about $7-$10 billion annually.

However, there are two vital questions that Dangote, the federal government of Nigeria and their deal makers must answer. First, the refinery is expected to pump and refine 650,000 barrels of crude oil per day. Will it pay for the oil in dollars? Otherwise, the refinery will cut Nigeria’s flow of foreign exchange by over $60 billion annually. This is based on my estimate using data on oil prices and oil production.

Second, how will the pump price be set? If the government steps back from its refining business and therefore stops setting the pump price as it is currently doing, Mr Dangote could rule the Nigerian oil market.

•Written By Zuhumnan Dapel

Twitter @dapelzg