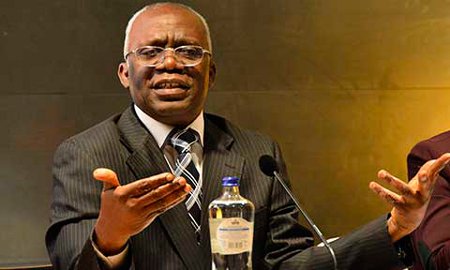

In this interview with OLADIMEJI RAMON, human rights lawyer, Mr Femi Falana (SAN), speaks on the false asset declaration charges filed against the Chief Justice of Nigeria, Justice Walter Onnoghen

Will you say the judiciary is on trial with the CJN’s case?

For sure, I believe that the nation’s judiciary is on trial. Although the Chief Justice of Nigeria is not one of the public officers covered by immunity in Section 308 of the Constitution, it is anomalous to parade him before a criminal court or a quasi-criminal court. Because the Chief Justice is the principal interpreter of the law he cannot afford to break the law. His integrity must be intact and as such he has to be above board like Caesar’s wife. As the primus inter pares among all judicial officers in the country he is required to lead by example. Since the Chief Justice heads the juridical organ of the state, charging him at the Code of Conduct Tribunal for alleged contravention of the Code of Conduct Act has put the entire judiciary on trial.

The judiciary has been on serious trial on three occasions in the past. The first time was when the Chief Justice, Prof Taslim Elias, was summarily removed from office by the Murtala Mohammed military regime during the 1975 purge of the public service. Even though the CJN was not specifically accused of engaging in corrupt practices he was sacked over his ex cathedral statement stopping the filing of affidavits to expose corrupt public officers by concerned citizens under the Yakubu Gowon regime. The second time was when Justice Ayo Salami, the then President of the Court of Appeal, accused Chief Justice Aloysius Katsina-Alu of perverting the course of justice in the appeal arising from the Sokoto State governorship election petition in 2011. The crisis shook the judiciary to its foundation. The third occasion was when the armed operatives of the State Security Service carried out a nocturnal raid on the homes of some judges on October 8, 2016 on the grounds of alleged corruption. The judges were arrested, detained and dragged to criminal courts to face corruption charges. This is the fourth time and it is the most trying period for the judiciary in the chequered history of the nation.

Many lawyers have accused the Buhari regime of intimidating lawyers and judges by charging them with criminal offences. Do you share the view?

The facts on the ground do not justify the allegation. I have observed a proclivity on the part of some senior members of the legal profession to practise law in an atmosphere of impunity. At the annual conference of the Nigerian Bar Association which held in Port Harcourt, Rivers State in 2006 or thereabouts, there was a heated debate by lawyers over the decision of the EFCC to charge lawyers with money laundering and allied offences. At the end of the debate there was a move to pass a resolution asking (former) President Olusegun Obasanjo to remove Mallam Nuhu Ribadu as the Chairman of the EFCC at the material time. I was in the hall when (the late) Chief Gani Fawehinmi called to find out what was amiss. As soon as I briefed him he roared like a lion in his condemnation of the reactionary resolution. Since lawyers are not above the law of the land I mobilised young lawyers at the conference to ensure that the resolution was defeated. It is part of our political history that long before the current political dispensation, judges and lawyers had been charged with criminal offences and arraigned in courts in this country. The earlier that lawyers are reminded that heavens did not fall when a couple of sitting judges were charged with murder and armed robbery in the 1980s, the better for the legal profession. In the same vein, scores of lawyers who were alleged to have contravened the penal and criminal codes have been put in the dock. Some were acquitted while those who were convicted were derobed and removed from the roll of legal practitioners.

On May 19, 1992, the late Chief Gani Fawehinmi (SAN) and I together with three other comrades were suddenly removed from Kuje Prison where we had been detained and taken before a Gwagwada Chief Magistrate Court where we were charged with the grave offence of treasonable felony. Can you imagine that civilians were charged with attempt to remove a military dictator from power? Even though the charge was served on us in the precincts of the court Chief Fawehinmi and I represented ourselves and the other defendants. Because we took advantage of the opportunity of asking for our bail to put the Ibrahim Babangida junta on trial in the course of our submissions the case was abandoned and the charge was eventually dismissed in our favour. The following year, Chief Fawehinmi, the late Dr Beko Ransome-Kuti and I were again arrested in Lagos for organising the mass protests which greeted the criminal annulment of the result of the June 12 presidential election. We were taken to a Magistrate Court in Abuja where we were charged with unlawful assembly, incitement and sabotage of the political transition programme. If lawyers and judges do not want to be paraded in criminal courts like common felons, the NJC and the NBA have to sanction members who breach the ethics of the legal profession.

Was the Court Appeal right in its pronouncement that a sitting judge cannot be tried in court until he has been probed and sanctioned by the NJC?

Certainly the Court of Appeal was palpably wrong. With profound respect, I do not agree with the judgment of the court in the case of Nganjiwa v Federal Republic of Nigeria, which held that a judge who has not been investigated and indicted by the NJC cannot be charged or arraigned in a criminal court or quasi-criminal court. As a matter of fact, the judgment appears to have glossed over the several decisions of the Supreme Court which have prohibited administrative or executive bodies from usurping the exclusive powers of the courts by trying public officers accused of committing criminal offences. It is not right that the judgment has conferred semi immunity on judges contrary to the provisions of section 308 of the Constitution. But whether we like it or not that remains the law until it is set aside. It is however pertinent to note that there is an exception recognised by the judgment. It is to the effect that judges who commit crimes outside the scope of their duties may be arrested and prosecuted by any of the law enforcement agency without any recourse to the NJC.

When the cases pending against judges were struck out in the trial courts on the authority of Nganjiwa’s case last year the EFCC filed an appeal against the judgment. The appeal is being handled by a team of lawyers led by my respected colleague, J.S. Okutepa (SAN). In the interim, the EFCC has referred the complaints of misconduct levelled against the judges to the NJC. From the information at my disposal the NJC has concluded the cases of not less than three of the judges and recommended their removal from the bench.

Don’t you think that the judgment of the Court of Appeal in Nganjiwa’s case was a ploy by the judiciary to shield its own?

In actual fact, I wrote a critique of the judgment when it was handed down. Rather than shield judges from prosecution it has exposed them to double jeopardy. A judge who is accused of committing a criminal offence in the course of duty is investigated for misconduct by the NJC. If found guilty the judge is recommended for removal and then thrown to the lion’s den as it were. Even if the allegation is dismissed and the judge is given a clean bill of health by the NJC the Attorney General of the Federation cannot be prohibited from filing a criminal charge if there is a reasonable suspicion that an offence has been committed by the judge. In other words, the power conferred on the Attorney General by Section 174 of the Constitution to initiate criminal proceedings against a criminal suspect cannot be stopped by the finding of the NJC or any of the executive bodies created by section 153 of the Constitution. But if a judge who is charged with corruption before a criminal court is interdicted or suspended by the NJC he or she may be freed by the trial court on technical grounds or due to lack of sufficient evidence to sustain the charge. And once the judge is discharged and acquitted by a criminal court that ends the matter. Having been freed by the trial court the judge will be automatically reinstated. That was what happened when a judge of the federal high court and his wife were recently charged with corrupt practices in the high court of the federal capital territory. As soon as the trial court freed the couple the judge was reinstated but if the case had been sent to the NJC he would have been removed from the bench before the trial. As far as I am concerned, the Nganjiwa’s case is a double-edged sword. It is hoped that the Supreme Court will reverse the dangerous judgment.

You described the charges against the CJN as illegal, saying he ought to be reported to the NJC. If the CJN is taken before the NJC do you think that the outcome will be objective?

Since fidelity to the rule of law does not allow the government to resort to self-help, the rights and obligations of every citizen must be determined in accordance with the law. The government cannot be so much in a hurry to engage in jungle justice in the trial of the Chief Justice or any other citizen. Hence, I had advised the Federal Government to withdraw the petition and refer the case to the National Judicial Council. Until the decision of the Court of Appeal in Nganjiwa’s case is overruled by the Supreme Court the Code of Conduct Bureau is legally obligated to report judges who either made false declaration or failed to declare their assets to the NJC. A couple months ago, the case of the Federal Republic of Nigeria v. Justice Ngwuta instituted by the Code of Conduct Bureau was struck out by the Code of Conduct Tribunal on the authority of Nganjiwa v Federal Republic of Nigeria. To the best of my knowledge the Code of Conduct Bureau has not filed any appeal against the decision.

Of course, it is not in dispute that the NJC is headed by the CJN but that does not preclude aggrieved parties from reporting allegations of misconduct against His Lordship to the NJC. If the NJC has to consider any allegation of misconduct against the CJN, His Lordship cannot preside over the meeting or the proceedings in line with the elementary tenet of natural justice which is that he cannot be the judge who will determine his own case. The principle is known as nemo judex in causa sua. Many Nigerians have quickly forgotten that when Justice Ayo Salami, former President of the Court of Appeal, accused the former Chief Justice, the late Justice Aloysius Katsina-Alu, of perverting the course of justice in the appeal arising from the Sokoto State governorship election petition in 2011 the Chief Justice had to recuse himself from presiding over the proceedings of the NJC on the matter. Even though the NJC hastily suspended Justice Salami for embarrassing the judiciary the complaint was eventually resolved in his favour. At the end of the marathon inquiry the NJC recommended the reinstatement of Justice Salami but the recommendation was ignored until the respected jurist retired when he attained the mandatory age of 70 years. It is on record that the Salami/Katsina-Alu imbroglio substantially eroded public confidence in the nation’s judiciary. It is therefore interesting to note that the particular political party and members of the legal profession who prevailed on President Goodluck Jonathan not to recall Justice Salami in line with the recommendation of the NJC have suddenly become the defenders of the independence of the judiciary in Nigeria. However, in view of the fact that the CJN has reacted to the allegation in writing the NJC, if given the opportunity, will have no choice but to decide the matter speedily in the interest of the judiciary and the country. Since this is a matter of public interest I have no basis to doubt the objectivity of the NJC in handling the matter.

Do you think the charges against the CJN might be a plot by the ruling party to have control of the judiciary against the coming elections?

I do not know the basis for the speculation. It is on record that Justice Walter Onnoghen, along with Justice Adesola Oguntade and Justice Aloma Muktar, who later became the first female Chief Justice, delivered a dissenting judgment in favour of candidate Muhammadu Buhari in the Buhari/Yar’Adua presidential election petition in 2007. If the ruling party wins the forthcoming presidential election, the Supreme Court cannot afford to annul it. Frankly speaking, the Onnoghen-led judiciary is not ideologically antagonistic to the Buhari administration. In fact, in prosecuting the anti-corruption agenda of the Buhari regime, the judiciary has largely collaborated with the executive. For example, when the National Assembly refused to pass the bill for the establishment of an anti-corruption court the Chief Justice suo motu directed all heads of courts to create special judicial divisions to hear corruption cases alone. The special judicial divisions have been established and they are working in the respective high courts. Even both the Supreme Court and the Court of Appeal have set up special panels to hear corruption matters. No doubt, a couple of important cases have been lost by the Buhari regime in recent time but it is not an expression of ideological disagreement. Ours is not like the Supreme Court of the United States of America whose decisions are largely anchored on political considerations. (Punch)