Survival of African democracies and the ‘Trump Syndrome’

Africans always look forward to advanced democracies, especially the United States, for answers to the continent’s problematic electoral processes. President Donald Trump’s handling of this year’s election has shown that the survival of democracies on the continent needs more than outside factors, writes Foreign Editor BOLA OLAJUWON

In nearly 12 months, about 17 African countries had conducted one form of election or the other, in which millions of voters went to the polls to elect their leaders. Two more – Niger Republic (December 27) and Central African (Dec. 27) – will go to the poll before the end of the year.

This year, presidential and, in some cases, parliamentary elections have been held in Burkina Faso, Burundi, Central African Republic, Cote d’Ivoire, Ghana, Guinea, Niger, Seychelles, Tanzania and Togo.

Parliamentary elections also took place in Chad, Mali, Ethiopia, Cameroon, Comoros, Egypt, Somalia, Liberia and Gabon.

A majority of the elections in 2020 were held in countries confronting or emerging from conflicts, including Burkina Faso, Burundi, the Central African Republic, Côte d’Ivoire, Ethiopia, Niger and Somalia. These countries face crises sparked from previous exclusive power structures, militant Islamist insurgencies and the challenges of building inclusive national visions from polarised polities. Consequently, the link between governance and security in Africa was displayed in most of the 2020 elections.

The elections were clustered in West Africa (with six elections), the Horn of Africa (Ethiopia and Somalia) and the Great Lakes (Burundi and Tanzania).

Election outcomes in few African countries in 2020

Cameroon elections: A vote marked by violence and abstention

Cameroon voted on February 9 in elections, which were postponed twice. With opposition boycotts, separatist intimidation and fears of violence, enthusiasm to vote were lacking.

Political analyst Stephane Akoa was surprised by the pre-election atmosphere in Cameroon’s capital, Yaounde. “When I look around, I see people on cafe terraces eating and drinking — but no posters and no campaigners with honking cars. It’s all very quiet,” he said.

Before the vote, Erick Essousee, the director of Cameroon’s electoral board, Elecam, insisted that elections could take place across the country. But in Cameroon’s two conflict-ridden English-speaking Southwest and Northwest regions, it was not calm when people went to vote in municipal and parliamentary elections.

At the end of 2019, when President Paul Biya began the election process, separatists who want an independent state for Cameroon’s generally marginalised English-speaking population called for a complete boycott of the polls and openly threatened those who wished to take part. But, to enforce an atmosphere of stability, security agents pounced on people and the opposition.

Côte d’Ivoire

Côte d’Ivoire’s presidential elections election was held on October 31 and at the end of an electoral campaign boycotted by the opposition, the outgoing President Alassane Ouattara was re-elected to a third term with 94.27%, according to provisional official results announced by the Independent Electoral Commission.

While the election was marked by the “active boycott” of the opposition, it was not surprising that Ouattara was re-elected for a third term.

Amnesty International reported that policemen in Abidjan, the Ivorian capital, allowed groups of men, some armed with machetes and heavy sticks, to attack protesters demonstrating against Ouattara’s third term bid reminiscent of the crisis that led to the ouster of his predecessor, Laurent Gbagbo.

Ghana

After Ghana’s Dec 7 elections, opposition National Democratic Congress (NDC) leader John Mahama, 62, rejected the officiate results of presidential and parliamentary exercise, citing “litany of irregularities and blatant rigging,” in favour of incumbent President Nana Akufo-Addo of the New Patriotic Party (NPP). It was the eighth presidential and parliamentary election since Ghana’s Fourth Republic was born in 1992, putting an end to military coups that truncated the First Republic on February 24, 1966, the Second Republic on January 13, 1972 and the Third Republic on December 31, 1981.

The Electoral Commission (EC) declared Akufo-Addo, 76, re-elected with 51.59% of the votes against Mahama’s 47.36%. The commission later revised the figure of valid votes cast but insisted the revision and the unincluded results of Techiman South constituency, where balloting was marred by violence, would not alter the declared results.

The NDC is contesting the EC’s figures and calling for a re-run, because, from the party’s calculations, none of the 12 candidates had met the constitutional requirements to be declared a winner.

The party also claimed that it had won 140 of the 275 parliamentary seats contested, against the 136 declared by the EC for it and 137 for the ruling NPP.

The police confirmed that at least five people were killed and 60 injured in the electoral violence, with two polling officials also arrested for vote tampering.

Burundi

Also in Burundi, the ruling party candidate won the presidential election, securing 68.72% of the vote.

Evariste Ndayishimiye, a retired general, took over from President Pierre Nkurunziza, after he beat the main opposition candidate, Agathon Rwasa, and five others, avoiding a runoff by securing more than 50% of the vote. Nkurunziza, who had been in power since 2005, decided not to stand for a fourth term and had dubbed Ndayishimiye his “heir.

Rwasa, president of the National Council for Liberty (CNL), described the results as “fanciful” and accused the government of “cheating” and “pure manipulation”. Burundi also shut the door to record a peaceful transition between two governments.

Burkina Faso

However, on November 26, Roch Kabore won a second term as Burkina Faso’s president, securing a solid mandate for himself and his party in an election deemed by international observers to be mostly free and fair. Kabore’s re-election in the conflict-hit country came despite poor approval ratings for the government’s performance on tackling spiralling violence that has caused a snowballing displacement crisis involving more than one million people and prevented hundreds of thousands of citizens from casting ballots last month. The biggest challenge in his second five-year term will be tackling the insecurity, which hampered the ambitious development goals he set out on coming to power and continues to tear at the social fabric of the country.

Since 2015, armed groups linked to banditry, al-Qaeda and ISIL (ISIS) have overrun large portions of the country’s north and east. More than 2,000 people have been killed due to the conflict this year alone.

Commentators said Burkina Faso has become the epicentre of the wider war against armed groups in the western Sahel. One of Kabore’s crucial political and military strategies has been the creation of a security “bubble” around the country’s major cities. The military has fortified Burkina Faso’s central plateau region, a natural bulwark between the capital, Ouagadougou, and the conflict raging in the north.

Tanzania

On Thursday, November 5, Tanzania swore in incumbent President John Magufuli for a second term. The inauguration took place amid a background of continuing challenges from the opposition party, which alleges voting irregularities during the October 28 vote. Several other nations, including the United States, supported the claim. Pre-election claims of both media suppression and social media blackouts were also widespread, though the election itself was conducted peacefully.

The country’s electoral commission announced that Magufuli won the contentious race with 84 per cent of the vote. Not long after the results were announced, the leaders of the opposition parties -CHADEMA’s Tundu Lissu and ACT Wazalendo’s leader Zitto Kabwe, among others – were arrested. Magufuli’s CCM party also won a significant majority in the country’s parliament, raising concerns from critics that he would use this overwhelming majority to try to extend his time in power past the current two-term limit, although the incumbent has stated that he did not plan to pursue such a path.

Is it yet Uhuru with African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance?

But, as was seen in the elections in Africa, it’s never quite that straightforward even as some progress has been made despite the countries appending their signatures and domesticating the African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance (ACDEG) and the African Governance Architecture (AGA) adopted by the Eighth Ordinary Session of the African Union Assembly held in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia on January 30, 2007.

The charter seeks to promote adherence, by each state party, to the universal values and principles of democracy and respect for human rights; promote and enhance adherence to the principle of the rule of law; premised upon the respect for, and the supremacy of, the Constitution and constitutional order in the political arrangements of the State Parties; promote the holding of regular free and fair elections to institutionalise legitimate authority of representative government as well as a democratic change of governments.

It prohibits, rejects and condemns unconstitutional change of government in any member state as a serious threat to stability, peace, security and development; promotes and protects the independence of the judiciary; nurture, support and consolidate good governance by promoting democratic culture and practice, building and strengthening governance institutions and inculcating political pluralism and tolerance; among others.

The essence of the ACDEG, according to political scientists, is that African countries had mostly halted the trend of violent coups, which was rampant between the 1960s and the early 1990s. But, sadly too, military dictators have since been replaced by imperial presidents with their version of democracy designed to keep them perpetually in power.

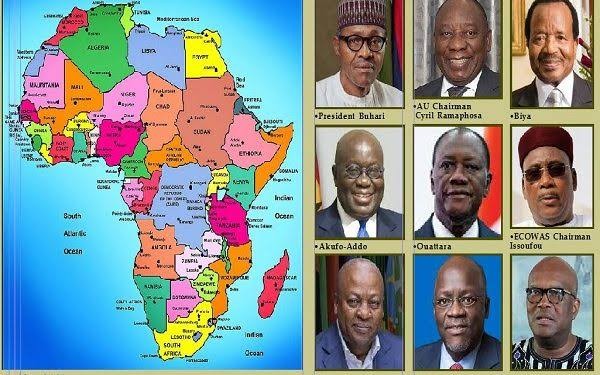

Unsurprisingly, Africa is home to six of the world’s 10 longest-ruling non-royal national leaders with Cameroon’s Biya leading the pack. Other sit-tight leaders who violate human rights like President Teodoro Mbasogo of Equatorial Guinea, Alpha Condé of Guinea and Rwanda’s Paul Kagame and Yoweri Museveni of Uganda (since 1986) are some of the African leaders, who need to be eased out of power. Another sit-tight leader, Algeria’s President Abdelaziz Bouteflika, was declared incapable of carrying out his duties and forced out of power after suffering stroke for a while.

An international affairs expert and consultant to international organisations on corporate communications and elections, Paul Ejime, in an interview with The Nation, said: “Political experts and analysts have noted that elections have become a source of political conflicts in Africa because of the characters and attitudes of politicians. When presidential candidates concede defeat, it is celebrated. President Goodluck Jonathan did that in Nigeria in 2015. Remember also Ghana in 2012, when John Mahama and Nana Akufo-Addo first ran against each other, Mahama won.

“In 2016, Akufo-Addo won. Also remember Malawi when opposition leader, Lazarus Chakwera, won the country’s rerun presidential vote. He defeated incumbent Peter Mutharika with 58.57% of the vote, according to the electoral commission. But in many African countries, some election cases ended at the Supreme Courts.

“Political analysts and watchers have questioned how open the political space was and still is in each African country. During the electoral period, African leaders have taken to shutting down the social media as seen in Uganda, Chad, Gabon, Burundi and Togo and most North African countries.

“Beyond the usual mix of ethnic and religious debates and rivalry in African national elections, other factors have had an impact on both the outcome and perception of the outcome of elections.

“You mentioned the African Charter on Good Governance. Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) also has Supplementary Protocol on Good Governance, which also spells out zero-tolerance for taking power through unconstitutional means. If it is through coups, it would not be recognised. Despite that, we saw that in Mali, there was a coup in August. Therefore, it is not yet Uhuru; African countries till have a long way to go.”

Trump refusal to concede: A bad example for Africa?

Former American President Barack Obama, in a powerful speech he delivered to Ghana’s parliament in 2009, said: “Africa does not need strongmen, it needs strong institutions.” It was, therefore, inconceivable that despite his apparent defeat, President Donald Trump sought to leverage the power of the Oval Office in an extraordinary attempt to block President-elect Joe Biden’s victory. He summoned a delegation of a battleground state’s Republican leadership, including the Senate majority leader and House Speaker, in an apparent extension of his efforts to persuade judges and election officials to set aside Biden’s 154,000-vote margin of victory and grant Trump the state’s electors. It came amid mounting criticism that Trump’s futile efforts to subvert the results of the 2020 election could do long-lasting damage to democratic traditions.

Trump’s efforts extended to other states that Biden carried as well, amounting to an unprecedented attempt by a sitting U.S. President to maintain his grasp on power to delegitimise his opponent’s victory in the eyes of his army of supporters.

The Supreme Court final repudiation of Trump’s desperate bid for a second term not only shredded his effort to overturn the will of voters: It also was a blunt rebuke to Republican leaders in Congress and the states that were willing to damage American democracy by embracing a partisan power grab over a free and fair election.

Like the rest of the world, Africa has been paying close attention to the U.S. election, since the U.S. still wields significant influence on what happens there. It’s the global policeman of democracy!

“Whoever is in charge in Washington and the policies they pursue have direct and indirect consequences for the continent,” Achille Mbembe, a Cameroonian political analyst, said.

“Many Africans look at the U.S. elections in a very cynical way — cynical in the sense that they know what stolen elections are all about,” Mbembe said.

Why African elections still have a long way to go

Looking at election outlook in Africa, Ejime said it is not yet Uhuru, insisting that African elections still has a long way to go.

He said: “There are triggers and drivers of conflicts in Africa. It is unfortunate that poverty, economic deprivations and lack of social safety net, intolerance by politicians and cronyism are affecting good governance in Africa.

“Ghana used to be a shining light, we saw what happened in the December 7 presidential and parliamentary elections, where violence was recorded. Five to six people were killed, according to the police. It is also likely that the matter will end up at Supreme Court. I once wrote an article on whether the judiciary is a facilitator or hindrance to democratic governance in Africa. There is also the syndrome of the third term by sit-tight leaders in Africa, who tinker with the constitution in a way it would favour them through getting their parliamentary majority to rubber-stamp changes in constitutions. In their desperation to cling on to power, you will realise that the changes they made are not even effective and sometimes half-baked, leaving lacunas for the incumbent to perpetuate himself in power.”

Ejime is right since the hallmark of democracy is the successful transfer of leadership from one government to the other through the conduct of credible elections and the understanding that the continued survival of a nation is not dependent on any single individual but the will of the people. But, “many African leaders have failed to imbibe the democratic culture as they continue to devise means to hold on to power, usually by playing with their nation’s constitutions through the connivance and acquiescence of weak, rubber-stamp parliaments, as well as a complicit judicial arm,” a report indicated.

This is noticeable in countries like Togo, Rwanda, Congo, Burundi, Equatorial Guinea, Chad, Djibouti, Zimbabwe, Uganda, Cameroon and lately, Guinea and Cote D’Ivoire. It is not surprising that in Eritrea, where no presidential election has taken place since independence in 1993, President Isaias Afwerki has remained the first and only president.

President Muhammadu Buhari (retd), while looking at the trend, warned: “It is important that as leaders of our individual member-states of ECOWAS, we need to adhere to the constitutional provisions of our countries, particularly on term limits. This is one area that generates crisis and political tension in our sub-region.”

A former Director-General, Nigerian Institute of International Affairs (NIIA), Prof. Bola Akinterinwa, while reacting to the sit-tight syndrome of African leaders, said the leaders’ penchant for remaining in power was an abuse and exploitation of democratic freedom and a major dynamic of development setback for Africans.

Akinterinwa said: “Sit-tight politics must be set aside by all means. Election rigging in all its ramifications, and particularly the issue of ill-defined citizenship, must be resisted by all means. These are three major dynamics of development setbacks that must be removed before a people-driven democracy can be truly established in Africa and before the prevalent democracy of injustice and unfairness, which have come to characterise intra and inter-African politics, can be stopped.”

Late Ghanaian President Jerry John Rawlings, once told a delegation of a civil society group, the African Forum on Religion and Government (AFREG): “Some people say I could have abused the constitutional order and stayed on, but I tell them I couldn’t because I had empowered the people. When you empower people you make them positively defiant so they will stand up to you when you try to misbehave. But in some parts of Africa, we don’t empower; we disempower, so we can stay as long as we want and they can’t stand up to us.”

Therefore, former President of South Africa Nelson Mandela and Nigeria’s former President Goodluck Jonathan, who resisted the urge to hold on to power, are worth emulating and celebrated.

However, Niger Republic holds presidential polls on December 27 and the Central African Republic conducting presidential and legislative polls on the same day. Niger’s Mahamadou Issoufou is leaving office after two terms. The ruling party has nominated former Defence Minister Mohammed Bazoum as its candidate. In CAR, President Faustin Archange Touadera is also seeking re-election. One hope that the two elections will fare better and meet AU Charter and other regional protocols on good governance, free and fair elections. This can only be achieved through building of strong institutions and not strong men. (The Nation)