The mistake of 1966

At Independence on October 1, 1960, Nigeria, with three, and later, four regions, was erected on the pillar of true federalism. But, on assuming office, the first military Head of State, Major General Thomas Aguiyi-Ironsi, dumped the federal principle and adopted a unitary structure. Subsequent military regimes have built on that ‘political mistake’. The many constitution reviews since then have not reversed the horror of ‘unification.’ Deputy Editor EMMANUEL OLADESU traces the mistake of military intervention, which for years, has compounded the task of nation-building

FIFTY five years after, Nigeria is still in a fix. Although military rule is now old-fashioned, the bewildered country is yet to fully recover from its devastating effects. The federal principle was liquidated, making Nigeria, an amalgam of incompatible and highly heterogeneous social formations, to slide into an avoidable unitarist enclave, barely six years after independence. Since then, the retracing of steps has been difficult.

So impactful negatively has the military legacy been that, 21 years after the restoration of civil rule, the country has not recovered from the dominant culture of over-centralisation of power, which has made the component units puppets existing at the financial whims and caprice of the power-loaded distant government.

The puzzle is: when will true federalism be restored?

As Nigerians reflect on the coups and counter-coups of January 15, 1966, they agonise over the misadventure of the military interlopers, whose main legacy was the abolition of power devolution. The national question stares the beleaguered nation-state in the face. Some leaders even manipulate the agitation for devolution on the borrowed platform of restructuring for partisan reasons.

But, to observers, the solution to the fundamental issue appears elusive, making the diverse stakeholders, many who have lost national outlook, to push for the renegotiation of the basis for national unity and peaceful co-existence. Others are advocating for a loose federation, and even, disintegration or secession, without much reflection.

As Nigeria still fails to grapple with its fundamental identity, participation and distribution crises, its leadership has not been able to rekindle confidence about the prospects of unity in diversity, the inherent advantage of big economic market and the utility and combined strengths of its numerical strength.

The genesis was the mutiny by soldiers, who were fed up with the activities of politicians who promoted ethnicity, religious division, corruption and general maladministration. But, having displaced the legitimate authorities, they proceeded to wreck monumental havoc on the polity by pursuing an agenda, which made the antics of the civilian leaders a child’s play.

Many commentators have argued that the civilian government emphasised centrifugal forces in the political system. The polity was just evolving under Prime Minister Abubakar Tafawa Balewa. The first six years of democracy were turbulent. Many errors were made by the antagonistic leaders from diverse regions.

But, the first military regime built on this faulty foundation by stressing the same centrifugal forces in the various political associations of the diverse people of Nigeria.

The conspirators, led by Major Kaduna Nzeogwu, were bubbling with idealistic yearnings. They unmindful of the implications of their mission for the emerging federal country. Nzeogwu’s co-travelers were Chris Anuforo, Emmanuel Ifeajuna, Donatus Okafor and Wale Ademoyega. They marked down Balewa, the four premiers and some key ministers for elimination. Also, they planned to kill their superior officers, who were perceived as strong men capable of foiling the coup.

The mutineers succeeded in killing the Head of Government, the Minister of Finance, Chief Festus Okoti-Eboh, the Premier of the Northern Region, Sir Ahmadu Bello, and his Western counterpart, Chief Ladoke Akintola.

It appeared that the top civilian leaders were actually ignorant of where military control lay in constitutional reality; hence, they failed to avert the looming danger. The ceremonial President, Dr, Nnamidi Azikiwe, an Igbo, was abroad. The Premiers of the Midwestern and Eastern Regions, Denis Osadebey and Michael Okpara, also Igbos, were spared by the coup plotters. On that note, the North cried foul, saying that the plot had an ethnic colouration. As Balewa was being killed, he was said to have retorted in Hausa: “Ibo! Ibo! Ibo! Sai kun rasa wajen zama a Nijeriya (Igbo! You will lack any place to belong to in Nigeria).

The coup negated military professionalism. The coup plotters were motivated by similar coups in Egypt and Sudan, which brought down legitimate authorities. But, they exceeded their projections. They planned for killings. But, not all the targets were hit. The commission raised a serious ethnic question.

The coup also took its toll on the military. The casualties included Brigadier Zakari Maimalari of the Second Brigade, Col. Kur Mohammed, described by the British author, Trevor Clark, as an amiable, but self-indulgent Chief of Army Staff-designate, Brigadier Samuel Ademulegun of the First Brigade, Kaduna, who had alerted the Prime Minister to the impending doom, and Col. Ralph Sodeinde of the Training College, Kaduna.

Some authors have stated that Ironsi’s was also a target. But, he escaped, having left the wedding party organised by admirers for Maimalari and his wife for another one on the Elder Dempster Line Flagship, Aureol, at Apapa Wharf. It was also suggested that Col. Yakubu Gowon, who got the hint at the party, hurriedly left a night club. He gave the impression that he was heading for Ibadan, but later strategically diverted to Mushin, instead of returning to barracks. Nzeogwu’s friend, Olusegun Obasanjo, who had just returned to the country from abroad, was said to have been kept in the dark.

All the civilians and senior military leaders who lost their lives during the rebellion were not accorded ceremonial burial befitting men of honour. The new Ironsi government did not send any representative to their funeral ceremony.

Amid the conspiracy, the General Officer Commanding the Armed Forces, Major General Thomas Aguiyi-Ironsi, was on the sideline. But, he later emerged as the chief beneficiary of the mutiny, having capitalised on the gap in strategy by the mutineers.

What is the place of Ironsi in the history of Nigeria? He was a jolly good fellow; a good family man and a professional soldier. He made history as the first General Officer Commanding the Nigerian Armed Forces, after succeeding General Welby Everard, who was not keen about recommending him as a successor. His critics said he assumed political leadership without vision and plan. The circumstances of the time foisted the responsibility on his shoulders. Politically and administratively, his tenure was, uneventful. It was a period of strange experimentation when the command system in the military was replicated in public administration. Advocates of federalism believed that to the extent that he lacked the understanding of what can keep a highly heterogeneous society together, he was colossal failure. Also, to that extent, Ironsi, in their view, cannot be described as a giant of contemporary history.

In fact, his predecessor as GOC, a British General, had preferred Ademulegun, Brigadier Babafemi Ogundipe and Maimalari as successor, despite the gallantry of Ironsi during the Congo Peace-Keeping Operations. Former Information Minister Ayo Rosiji told his biographer, Dr Nene Uba, that what paved the way for Ironsi’s ascension was the pressure on the Prime Minister by the National Council of Nigerian Citizens (NCNC) ministers of Igbo origin, including Dr. Kingsley Mbadiwe and Mathew Mbu, to appoint him. Their argument was that juniors cannot be promoted above their seniors.

As the coup failed, the GOC seized the opportunity for military personality assertion. Many writers said he was an opportunist. It was evident, as a British commentator, Trevour Clark, put it, that the majority of the army would not join the rebels in a civil war between a Federal Government headed by the GOC and a murderous revolutionary government set up by a major in Kaduna.

Ironsi may have tricked the rebels to surrender. Already, there was a subsisting class war between him and these more educated rivals. The five majors were university graduates, unlike Ironsi, who felt that the civilian leaders foisted these young elite on him as junior officers. Nzeogwu, who was arrested and detained, protested in vain, saying: “We feel it is absurd that men who risked their lives to establish the new regime should be held prisoner by other soldiers.”

Ironsi also feigned loyalty to Balewa, whose whereabouts was known when he was seized by coup plotters. In that moment of anxiety, the cabinet was in disarray. A sort of succession struggle broke out between two ministers-Alhaji Bukar Dipcharima and Mbadiwe, and the Acting President, Dr. Nwafor Orizu, could not quickly name an Acting Prime Minister. The GOC cleverly conveyed the impression that the only route to stability and restoration of peace was to hand over the reins to him. Orizu had to later announce that he was advised by the Council of Ministers, led by Dipcharima, to voluntarily hand over to Ironsi to restore order and peace. The ministers surrendered under duress.

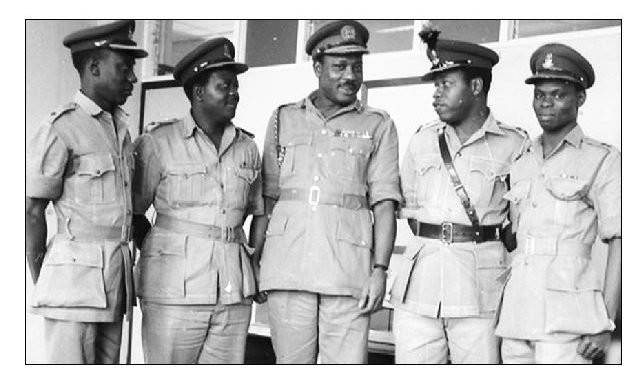

Ironsi may have lacked an advantage of political education and enlightenment. The newly designated Supreme Commander of the Federal Military Government made a public pronouncement of a seven-point programme. He decreed the suspension of the constitution and abolished the offices of the president, prime minister, governors, premiers and parliaments. He appointed military governors for the regions; Major Hassan Katsina (North), Lt.Col. Emeka Odimegwu-Ojukwu (East), Lt.Col. Adekunle Fajuyi (West) and Lt. Col. David Ejoor (Midwest). The deposed civilian governors were made advisers to them. Brigadier Babafemi Ogundipe became Ironsi’s deputy at the Supreme headquarters. Gowon, who was to succeed him six months later, was appointed as Chief of Army Staff.

Ironsi became the head of a country in turmoil. Yet, it appeared that he lacked a clear direction. In his book titled: ‘People, politics and politicians of Nigeria (1940-1979),’ Bola Ige, the bitter Publicity Secretary of the proscribed Action Group (AG), wrote: “What Ironsi did was to, as our peopl

e would say, eat with all ten fingers. He blackmailed Orizu, Inuwa Wada, Dipcharima and other ministers with the “coup” of five majors, and he blackmailed Nzeogwu with his “mutinous group” and the “government” that the Acting President had “voluntarily handed over to me.”

Apparently, the Head of State may have also been carried away by the pleasure of office. As Ige, who later became the governor of Oyo State in the Second Republic, put it: “Ironsi successfully hijacked the putsch of the five majors and proceeded to install himself in office. He moved into the State House at Marina, Lagos, and began a flamboyant lifestyle. He himself loved the bottle and he was not niggardly in the distribution of alcohol in that royal palace.

“Before long, Nigerians began to see something they had not been used to seeing before; the wife of a head of Federal Government strutting about in expensive clothes and headgear under the guise of doing one charitable thing or other. And a crowd of boot-lickers and mis-advisers descended upon Ironsi from among his Igbo people.”

The new administration was confused about urgent challenges of governance. Students and activists persisted in their clamour for the release of Nzeogwu, the symbol of patriotic pan-Nigerian fervour. The West was disappointed that Ironsi was silent about the fate of the jailed Lead

er of Opposition, Chief Obafemi Awolowo, their idol, in prison. Delegations from the various provinces in Yorubaland protested to Fajuyi, saying that his continued imprisonment was unjust. The Head of State turned a deaf ear. The perception of the North and the West was that the new regime was to the advantage of the East, the home region of the ruler. In fact, while reflecting on that period of national anxiety, Gowon told his biographer: “There were complaints that only Igbos came to advise Ironsi.”

In May and June 1966, there were massacres in the North and many Easterners were victims. The pogrom had started. Northern vocal voices unleashed the calls for “Araba;” thinking that secession was the final solution. Even, Suleman Takuma, who later become a presidential adviser in the Second Republic, placed an article in the Federal Government-owned newspaper, calling for the break-up of Nigeria. He was merely echoing what federal legislators from the North had demanded 13 years earlier when they were booed at the Lagos Airport on their way home after rejecting the motion for independence.

Of course, Northern military officers suspected that Ironsi had hand in the coup, simply because it was largely perceived as an Ibo plot. Although the four military governors understood governance better, their efforts at calming down tensed nerves were not matched or complemented by any logical understanding of the grave challenges by the Supreme Commander. The military leader was in a precarious situation. Since Ironsi was reluctant to punish the executors of the coup that brought him to power, the Northern officers were angry, thinking that he had encouraged indiscipline and disloyalty. But, if he had wielded the big stick, Southerners who saw the coup as a revolutionary move would have also been offended.

Reflecting on Ironsi’s tenure, eminent scholar Prof. Isawa Elaigwu noted that, though the nature of the coup became more suspicious to many Nigerians, the Head of State’s subsequent actions only aggravated it. “In a way, it may be argued that General Ironsi was a victim of circumstances-circumstances which required the quick use of his mental capacity and political subtlety-two traits Ironsi did not posses in adequate amounts,” added the political scientist in his book: ‘Gowon: The biography of a soldier-statesman.’

Elaigwu suggested that the political pulls within the system may have made Ironsi to vacillate in making radical changes in the Federal-Regional relations.

Ironsi later took some steps. But, to the public, they were not meaningful. He set up a constitutional review committee headed by the late Chief Rotimi Williams. He mooted the idea of a curious decree that was not extensively debated by the Supreme Military Council and the fractional Federal Executive Council, which was later set up. The report was to be submitted to another Constituent Assembly, and the outcome was to be subjected to a referendum. But, it took the Head of State three months to make any political move. He had no council of ministers to assist him in navigating the difficult ship of state for months. In that state of inaction and confusion, it took him five months to opt for what Elaigwu described as “grater centralisation of power through unitarism.”

The turning point in the full military explosion was the enactment of the Unification Decree Non.34, 1966, which effectively made Nigeria a unitary state. It was worrisome that the negative restructuring was embarked upon without waiting for the report of the committee chaired by Williams. In his May broadcast, Ironsi declared: “Nigeria shall on the 24th May, 1966 ceased to be a federation and shall accordingly as from that day be a republic by the name of the Republic of Nigeria, consisting of the whole territory, which immediately before that day was comprised in a federation.”

As federalism was abolished, the regions ceased to exist. From their ashes sprang up a group of territorial areas called provinces. Each region became a group of provinces, with a National Military Government at the centre. Ironsi also proposed a new economic plan, which never saw the light of the day.

The Head of State rationalised the new measures. He explained that the decree was “intended to remove the last vestiges of intense regionalism of the recent past, and to produce that cohesion in the government structure, which is so necessary in achieving and maintaining the paramount objective of the National Military Government and national unity.

The most important element of the decreee was the unification of the civil service of the abolished regions. Ironsi said: “All officers of the Services of the Republic in a civil capacity shall be officers in a single service to be known as the National Public Service, and accordingly, all persons who immediately before were members of the public services of the Federation or of the public service of a region shall become members of the National Public Sevice.”

When Northern monarchs raised an eye brow over the unification, Ironsi replied that the National Government was not interested in running five governments(a central and four regional governments) and consequently, five civil services.

The decree created a nation, but failed to accord priority to unity in diversity required in a heterogeneous country. The quest for a union by the political elite may have been uncritically confused with an academic demand for unity. Cohesion is an attribute of a united country, but it cannot be forced or imposed. Therefore, popular feelings in the North and the West underscored dejection and disillusionment. There was a propaganda in the North that civil servants from the South will invade the North to displace Northerners from the public service because they had more professional expertise. The rumour was not dispelled.

For the Northerners, the unification of the civil service was the most annoying aspect of the decree. On May 27, 19666, riots broke out in the North in which many Easterners (mainly Ibos)were killed. The nature of the problem on ground also exposed the fragility of the military as soldiers were not indifferent to the wrong steps taken by the military leader. They believed that Ironsi had further sowed the seed of discord and violence. It thus became difficult to deploy the partisan military to quell the riots. Col. Fajuyi’s and Col. Katsina’s wise counsel that Ironsi should have a rethink about the unitary decree was ignored. In frustration, Katsina, a prince, remarked: “The egg has been broken.”

Ironsi’s appointments also mirrored ethnic leaning. He replaced the Attorney-General, Dr. Teslim Elias, with Onyiuke. Another Igbo, Nwokedi, was appointed as the Sole Administrator on Unification of Civil Service. Dr. Pius Okigbo became the Economic Adviser. Then, contrary to Katsina’s advice, he attempted to appoint Prof. J.C. Edozien from the University of Ibadan as the Vice Chancellor of the Ahmadu Bello Universoty, instead of Prof. Ishaya Audu. When he effected promotions in the Army, of the 21 officers promoted from Majors to Lieutenant-Colonels, 18 were Ibo-speaking.

Had Ironsi harkened to the demand for state creation, the tension would have subsided. Perhaps, the subsequent civil war could have also been averted. The minority groups, who were marginalised under the abolished regions, would have heaved a sigh of relief. Sectionalism would have been curtailed to an extent.

In six months, the Ironsi regime, which had been swimming in legitimacy crisis, finally lost credibility. Berating his sense of judgment, Elaigwu noted: “Political engineering demand the ability to know the environment well, to feel the political temperature of the system, and to know the limits to which decisions can be taken without threatening the basic consensual values which bind the society together.”

As the disquiet persisted, Ironsi took two steps. He asked Gowon, who enjoyed popularity among military officers, to douse the tension in the Army by explaining the situation to the Armed Forces, in a bid to retain their loyalty. He also embarked on tour of the country to explain the activities of his government to the traditional rulers. He returned from the North to Lagos, and left for Ibadan. After meeting the obas, a cocktail party was organised for the Head of State by his host, Fajuyi, unmindful of the plan for a bloody and vengeful coup by Northern officers, led by Yakubu Danjuma and Lt. Walb. Major Akahan, the Army commander at Ibadan, who claimed that he was helpless when Ironsi was seized by the coup plotters.

It was evident that the July 29,1966 coup was a retaliation coup to avenge the blood of Balewa, Sardauna and other Northern military officers killed during the January 15 coup. The protectors of the Supreme Commander became his captors. An account said that Fajuyi protested that Ironsi should not be killed in Ibadan where he was hosting him. Both Ironsi and Fajuyi were shot dead near a stream in a nearby bush along the Railway crossing, Olodo, on the way to Iwo. With the fall of Ironsi, an angry Muritala Muhammmed, who also inspired the military avengers, was pacified.

Simultaneously, violence engulfed some barracks in the North and South where Northern officers murdered their Southern counterparts, particularly Ibos. The killings of Southern civilians also continued unabated in the North. Tension enveloped the country. Once again, Nigeria was on the brink. Many Easterners had returned home, but homeless. Their property had been destroyed in the North. Many children returned as orphans, their parents having been killed during the pogrom. The maimed cried for help. Thus, Governor Ojukwu had the problems of refugees on his hand. Curiously, the North started to change its tunes on Araba.

Ironsi’s exit heralded a succession crisis. As discipline broke down in military formations, Ogundipe attempted to summon a special meeting of senior Army officers in Lagos. But, to his consternation, a sergeant refused to obey his orders. Thus, reality dawned on him that his authority as the next-in-command was a farce. He turned to Gowon, who was not a party to the plot, to restore order. Ogundipe hurriedly left the country, only to emerge later as the High Commissioner to Britain. His departure from Nigeria beat the imagination of Ojukwu, who had expected him to succeed Ironsi. But, Chief of Naval Staff Admiral Akinwale Wey and other senior officers thought otherwise. It appeared to them that only a popular officer like Gowon could fit into the role. Yet, the military governor of Eastern State was not ready to accept Gowon’s leadership. That resentment, essentially, led to a chain of events which culminated into the 30-month old civil war.

Gowon embarked on populist programmes to get legitimacy. He displayed wisdom by retracing the steps of the National Military Government on the unitary system. He allowed the four governors to continue in their offices. Later, he upgraded some provinces into states, thereby winning the hearts of state creation agitators, especially in the minority areas. He released Awolowo and other political prisoners. He appointed credible political leaders-Awolowo, Anthony Enahoro, Aminu Kano, Joseph Tarkar, Ali Monguno, Okoi Arikpo-into his cabinet. Then, he dangled the carrot of transition programme at the political class.

However, the elements of the unitary system continued to characterise the military rule. The regions, and later, states lost their pseudo-autonomy. Unlike the First Republic, the governors took orders from the Commander-In-Chief in Lagos. Also, ego war between Gowon and Ojukwu climaxed into a full blown secession war, which claimed millions of lives. The setting up of a cabinet of non-professional soldiers angered some officers who continued to agitate for their inclusion in government.

In their attempts to resolve some problems, the military created fresh hurdles. State creation led to more demand for states, with successive military administrations creating unviable states. The exercise was also carried out with bias and sentiments, with each creation reinforcing the numerical superiority of the North over the South. State creation has been accompanied by local government creation. The exercise has also resulted into a lopsided distribution.

Also, the military has been reluctant to hand over power to civilians. As a political scientist, Prof. Bayo Adekanye, noted, reliquishing political control amounted to the self-liquidation of acquired power. Many have argued that the military became a source of division and inequity. Out of eight military Heads of State, only two were from the South. Not only did the military indulged in corruption, it also demonstrated its capacity for stifling the growth of democratic culture.

Ironsi promised a transient government, but with no concrete proof of intention. Gowon disappointed Nigerians in 1974 when he postponed the hand over date. Muhammadu Buhari did not contemplate any transition programme. Ibrahim Babangida’s transition programme amounted to deceit. The military president annulled the most credible and historic June 12, 1993 presidential election won by the late Chief Moshood Abiola of the proscribed Social Democratic Party (SDP). The late military Head of State, General Sani Abacha’s transition programme was aimed at self-succession.

However, despite the exit of the military from power, its legacy of unitarism has continued abated. Former Education Commissioner in old Western State, the late Sir Olaniwun Ajayi lamented that “some regional assets were nationalised without compensation.”

Up to now, the police is centralised, making local policing a herculean task. Even, the distant power-loaded Federal Government still has some measures of financial control over the local governments domiciled at the grassroots. Local governments are still listed in the constitution, a fact that underscores undue centralisation of power.

Also, revenue allocation has placed the states and local governments at the mercy of the all-powerful central government, despite the enormity of items on the Concurrent List for states and Residual List for local governments.

Fifty five years after, the agitation for political restructuring is more intense. “Injustice and lack of fairplay have continued to characterise the practice of federalism to the extent that people now demand for true federalism,” lamented an elder statesman, Ayo Adebanjo, who added:”There is no alternative to true democracy. It is the answer.”

The non-negotiable clamour for identity preservation, self-expression and the reshaping of distributive politics have generated much heat. The goal, in the view of political scientists Kunle Amuwo and Georges Herault, is to correct perceived structural defects and institutional deformities. They argued that “political restructuring is intended to lay an institutional foundation for a more just and a more equitable sharing of the political space by multinational groups cohabiting in the federal polity,” adding that the strategic objectives seem to be the solidifying-or perhaps, merely engendering-of a sense of national community.”

Scholars of federal principle, including Rotimi Suberu and Adigun Agbaje, have also noted that the ghost of a faulty federal foundation has continued to hunt Nigeria. They noted that “the Nigerian federation was established to ‘hold together’ the diverse ethnicities and nationalities that had been forcibly and arbitrarily incorporated into a Unitary Colonial State under British imperialism.” According to them, devolutionary federations like Nigeria tend to lack the integrative identities and the values of civic reciprocity and mutual respect associated with voluntary compact or bargain to join a federal union. Rather, they tend to be besieged by the disruptive local loyalties that made the constitutional fragmentation or disaggregation of the state necessary.

“Reflecting their unitary constitutional origins as well as the need to contain disruptive centrifugal pressures, devolutionary federations tend to develop relatively centralised constitutions and political institutions. In essence, ‘holding together’ federations like Nigeria tend to be more formally and institutionally centralised, but less politically integrated and structurally coherent than ‘coming together’ federations.”

As the push for ‘federal reform’ continues, a searchlight should be beamed on the revenue allocation to the tiers of government, based on fairness. This may be the best way to resolve what Suberu and Adigun called the crisis of distributive federalism.

The two scholars also made some suggestions critical to the resolution of the national question. These include: debate on the choice of the right system of government for Nigeria, whether parliamentary or presidential; the review of the allocation of constitutional responsibilities to the tiers, transparent administration of the Federation Account, discussion on the effectiveness and viability of the current state-structure, the power of control over local governments by the federal and states, and federal character and other power sharing practices.

Other thorny issues are the position of the Federal Capital Territory (fcT), state or community police, the status of Sharia, land tenure, and consolidation of democracy.

(The Nation)