Business

SEC’s capital hike puts survival of the fittest to the test

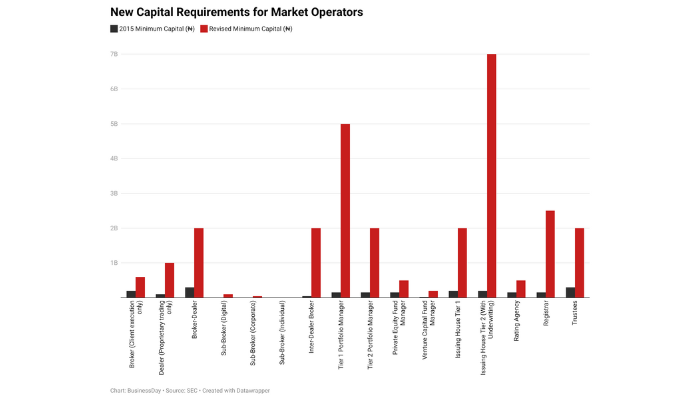

Nigeria’s securities regulator has unveiled its biggest market overhaul in more than a decade, hiking minimum capital thresholds for operators by as much as 40 times – or three times in the best case scenario – and setting a June 2027- deadline that is likely to force consolidation, exits and a smaller, more tightly capitalised industry.

The move is intended to harden the financial resilience of the market. Its likely effect, however, is to radically reshape who survives in it.

Under the revised framework, Tier-1 portfolio managers must now hold a minimum of N5 billion in capital, Tier-2 issuing houses N7 billion, and broker-dealers N2 billion – levels that would have seemed implausible only a few years ago. In some segments, the increase runs into the thousands of percentage points.

The SEC says the overhaul is designed to align capital adequacy with the evolving risk profile of market activities, strengthen investor protection and support innovation in emerging segments such as digital assets and commodities. “The revised minimum capital framework seeks to enhance the financial soundness and operational resilience of market operators,” the regulator said in a January 16 circular seen by BusinessDay.

All regulated entities – from brokers and issuing houses to fintech operators, virtual asset service providers and commodity intermediaries – must comply by June 30, 2027 or face sanctions ranging from suspension to outright loss of registration.

Market participants say the deadline effectively sets a countdown to a wave of mergers, quiet exits and forced restructurings.

Nowhere is the tension sharper than among asset managers and brokers. Tier-1 portfolio managers overseeing more than N20 billion in assets, or with foreign exposure of up to 40 percent, must raise capital from N150 million to N5 billion. Those managing over N100 billion are required to hold capital equivalent to 10 percent of assets under management – a dynamic requirement that scales capital needs upward as firms grow.

Critics argue that this approach misunderstands the nature of capital market risk. “Unlike banks or insurers, asset managers do not warehouse balance-sheet risk,” said Sola Oni, a chartered stockbroker and registrar. “They operate an agency model. Client assets sit with custodians. The principal asset here is trust and execution integrity, not leverage.”

For brokers, the arithmetic is even starker. Minimum capital for broker-dealers jumps from N300 million to N2b billion; dealers from N100 million to N1 billion; execution-only brokers from N200 million to N600 million. Sub-brokers– often the market’s retail-facing foot soldiers– face 10-fold increases. Inter-dealer brokers must now raise N2 billion, up from N50 million.

The concern, market veterans say, is not that capital standards should rise, but that the scale and timing of the increase may crowd out precisely the operators that broaden participation. Less than 10 percent of dealing firms on the Nigerian Exchange (NGX) account for more than 60 percent of traded value. These firms – well-capitalised, foreign-investor-facing and institutionally connected – will likely absorb the new requirements with relative ease.

The rest of the market serves a different function. “Who explains equities to teachers, civil servants, artisans and first-time investors?” Oni asked. “It’s the smaller brokers. If they disappear, market depth may improve statistically, but market inclusion will not.”

Issuing houses face a similar reckoning. Tier-1 firms providing advisory and non-interest finance services without underwriting must now hold N2 billion, up from N200 million. Tier-2 issuing houses — full-service underwriters — must raise N7 billion. For a market where deal flow remains episodic and margins cyclical, the capital hurdle raises questions about return on equity and long-term viability.

Supporters of the reform argue that fragmentation has stretched regulatory oversight and that consolidation could improve standards. “The reform is long overdue,” said Abiola Rasaq, former head of investor relations at UBA. “It signals regulatory seriousness and could strengthen the market’s long-term credibility.”

Still, Rasaq cautioned that timing matters. With banks only recently completing a sweeping recapitalisation, investor appetite for injecting fresh equity into private, non-listed market operators may be limited. Only a handful of firms, such as United Capital, have public market access.

More critically, the requirement for asset managers to seed growth with proportional capital injections could dampen expansion. “Every additional N10 billion in assets now implies N1 billion in new capital,” Rasaq said. “That is a material capital risk for leading managers and could discourage scale.”

Following the criticism of rules mandating fund and portfolio managers with assets above N100 billion to hold capital equal to 10 percent of their assets under management, the SEC clarified that the 10 percent figure was a clerical error.

The regulator explained that the intended requirement was 0.1 percent of NAV or AUM.

“It is however important to note that one or two typographical errors does exist especially for asset managers,” Emomotimi Agama, director-general, SEC, said in an interview on Arise TV.

Nigeria’s experience is not unique. Across emerging markets, regulators regularly revisit capital thresholds to reflect evolving market risks and product complexity. However, the scale, structure, and pacing of such reforms vary significantly.

In India, the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) is implementing a phased increase in net-worth requirements for merchant bankers involved in public offerings and underwriting. By 2027, firms will be required to hold a minimum net worth of ₹250 million ($2.8 million) rising to ₹500 million by 2028.

Advisory-only firms are subject to lower thresholds. The gradual rollout is designed to preserve market vibrancy while strengthening safeguards.

South Africa adopts a different approach. As the continent’s most developed capital market, it relies on risk-aligned capital and liquidity requirements. Capital levels are often linked to operating costs or liquid capital buffers rather than flat thresholds that far exceed industry norms.

Other emerging markets, including Malaysia, Morocco, Pakistan, and Romania, apply capital adequacy rules tailored to specific business models. These frameworks often combine minimum capital floors with ongoing capital-to-risk metrics, rather than relying solely on large upfront requirements.

Nigeria’s SEC insists the review aligns with its mandate under the Investments and Securities Act, 2025, and reflects how far the economy has evolved since 2015. Few dispute the need for reform. The unresolved question is whether capital has been calibrated as a scalpel– or wielded as a hammer. (BusinessDay)

-

Metro12 hours ago

Metro12 hours ago‘I Was In The Wilderness For 42 Days After Paying N17Million Ransom’ – Ekiti Farm Manager Narrates Kidnap Ordeal

-

News12 hours ago

News12 hours agoBanditry: Over 300,000 Displaced In Niger – Bago

-

News13 hours ago

News13 hours agoNo attempt to poison Tinubu – Presidency

-

News12 hours ago

News12 hours agoTinubu convenes Police Council today to confirm Disu

-

Politics12 hours ago

Politics12 hours agoINEC Can’t Guarantee Perfect Election In 2027 – Amupitan

-

News12 hours ago

News12 hours agoIran: IGP Orders Heightened Surveillance In North

-

Business12 hours ago

Business12 hours agoAbu Dhabi directs hotels to extend guests’ stay over travel restrictions, says it’ll cover cost

-

Metro12 hours ago

Metro12 hours agoKidnapped Ondo Man Killed, Found Dead In Edo Forest After Ransom Payment