Business

Dangote Cement: N760bn final dividend payout highest in history

Historical comparison …

The dividend will be paid to shareholders whose names appear in the Register of Members at the close of business on Wednesday, June 17, 2026.

The Register of Members will be closed on Thursday, June 18, 2026. By Thursday, July 2, 2026, dividends will be paid electronically to Dangote Cement shareholders whose names appear in the Register of Members as of Wednesday, June 17, 2026, and who have completed the e-dividend registration and mandated the Registrar to pay their dividends directly into their bank accounts.

The stock, which closed February at N779 per share, had reached a 52-week high of N829.5 as against a 52-week low of N425.

Last 7 Days Trades ….

The group’s operating highlights also show that Dangote Cement volumes were down by 0.9 percent to 27.5Mt. The Group dispatched 34 ships of clinker from Nigeria to Ghana and Cameroon. Nigeria’s cement and clinker exports went up 18.6 percent at 1.4Mt. Dangote Cement Plc also took delivery of an additional 1,600 CNG trucks to support cost savings; while also recording strong reduction in Nigeria’s cash cost due to a favourable energy mix.

Group revenue grew 20.3percent to N4.306trillion, driven by proactive management initiatives and resilient demand across markets. EBITDA increased by 43.4 percent to N1.981trillion, while profit after tax crossed the N1 trillion milestone for the first time — doubling 2024 performance.

This expansion in profitability, achieved despite a modest 0.9 percent decline in volumes to 27.5 million tonnes, reflects the company’s deliberate focus on margin discipline, cost efficiency, and value creation.

Dangote Cement is Africa’s leading cement producer with 55.0Mta capacity across Africa. A fully integrated quarry-to-customer producer, Dangote Cement has a production capacity of 35.25Mta in its home market, Nigeria. Dangote Cement’s Obajana plant in Kogi state, Nigeria, is the largest in Africa with 16.25Mta of capacity across five lines; the Ibese plant in Ogun State has four cement lines with a combined installed capacity of 12Mta; Gboko plant in Benue state has 4Mta; and Okpella plant in Edo state has 3Mta. Through Dangote Cement’s recent investments, the company has eliminated Nigeria’s dependence on imported cement and has transformed the nation into an exporter of cement and clinker, serving neighbouring countries.

In addition, Dangote Cement has operations in Cameroon (1.5Mta clinker grinding), Congo (1.5Mta), Ghana (2.0Mta clinker grinding and import), Ethiopia (2.5Mta), Senegal (1.5Mta), Sierra Leone (0.5Mta import), South Africa (2.8Mta), Tanzania (3.0Mta), Zambia (1.5Mta), and Cote d’ Ivoire (3Mta).

Arvind Pathak, Chief Executive Officer, Dangote Cement Plc said: “2025 was a landmark year for Dangote Cement as we delivered exceptional financial performance that underscores the strength of our business model and the effectiveness of our strategic initiatives.

“A key highlight of 2025 was the successful commissioning of our 3Mta grinding plant in Côte d’Ivoire during Q3. We are pleased with the ramp-up progress as the plant gradually scales toward full capacity utilisation. This strategic asset strengthens our West African footprint and positions us to serve growing demand across the region while benefiting from our integrated supply chain.”

“Our export strategy delivered strong results in 2025, with cement and clinker exports increasing 18.6percent as we executed 34 clinker shipments to Ghana and Cameroon. This performance reinforces our vision of positioning Nigeria as a low-cost regional hub and replacing expensive intercontinental imports with competitive African production.

“Our export terminals at Apapa and Onne continue to prove their strategic value, and we remain firmly on track to achieve our ambitious target of 10 million tonnes of combined exports by 2030. Cost leadership remains the cornerstone of our competitive advantage. In 2025, we accelerated our pioneering transition to Compressed Natural Gas (CNG) technology, acquiring over 3,000 full CNG trucks, the largest fleet deployment in Africa’s cement industry,” Pathak noted.

“These vehicles deliver over 60 percent fuel cost savings compared to diesel, embedding permanent structural advantages into our cost base. We are committed to converting our entire logistics fleet to CNG by 2027, a transformation that will further strengthen margins, enhance operational flexibility, and significantly reduce our carbon footprint.

“Looking ahead, we are confident in our growth trajectory and our ability to capitalise on Africa’s robust cement demand fundamentals. We will continue commissioning new capacity, including the transformational 6Mta Itori plant, while advancing expansion projects in Ethiopia, Cameroon, South Africa, Zambia and Senegal.

“Our focus remains on operational excellence, margin expansion through cost efficiency, and scaling our export business. With improving macroeconomic conditions across our key markets, the structural tailwinds from the African Continental Free Trade Area, and our unmatched competitive positioning, Dangote Cement is poised to deliver another year of strong performance and sustained value creation for our stakeholders,” he added. (BusinessDay)

-

Politics10 hours ago

Politics10 hours agoAPC Congress: Ogun, Lagos Retain Chairmen, Ondo, Oyo Elect Babatunde, Adeyemo

-

News10 hours ago

News10 hours agoDSS Arrests Police, Immigration Officials ‘Implicated’ In El-Rufai’s Return To Nigeria

-

News23 hours ago

News23 hours agoBREAKING: Tinubu nominates Oyedele as finance minister

-

Sports10 hours ago

Sports10 hours agoRonaldo ‘Flees’ Saudi Arabia Amid Bombardment From Iran

-

News10 hours ago

News10 hours agoRivers Assembly unveils Fubara’s commissioner nominees

-

News9 hours ago

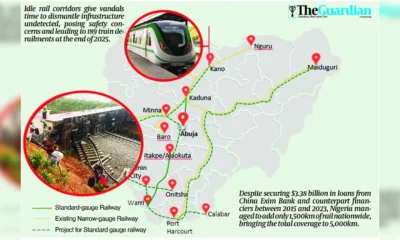

News9 hours agoFaulty design, vandalism, neglect endanger $3.4b rail overhaul

-

Business10 hours ago

Business10 hours agoBusinesses Bleed As Blackout Worsens

-

News9 hours ago

News9 hours agoFG suspends pilgrimages to Israel over Middle East security situation