Opinion

Restoring dignity, securing the future: The case for globally competitive academic salaries in Nigeria

In June 2025, a story circulated about a university professor who grows and sells vegetables at a local market in North-Western Nigeria. When I read the news, many thoughts ran through my mind. I imagined what it takes to cultivate vegetables; to package them carefully, ensure they reach the market fresh, wait for them to be sold, and then begin to plan another cycle of that same daily struggle.

Out of curiosity, I checked this professor’s research profile to confirm his academic credentials. He is a Professor of Plant Physiology, a field dedicated to studying the inner workings of plants, their growth, resilience, and genetic potential.

Yet, nowhere in his record did I find any scholarly work on plant marketing or entrepreneurship. It was reasonable to conclude, as indeed was later confirmed, that he turned to vegetable trading simply to survive. I must commend this professor for choosing survival over despair; for choosing dignity over cutting corners; and for walking the path of honour rather than retreating into the oblivion of regret. But this, sadly, is not a story of entrepreneurship. It is a story of systemic failure.

In the university system, attaining the rank of Professor is no ordinary achievement. It is the culmination of decades of rigorous teaching, painstaking research, and sacrificial service to both the academia and society.

Professors are the intellectual engine room of any nation: they generate new knowledge, push the frontiers of discovery, shape policy through evidence, and guide young minds into becoming tomorrow’s leaders. They are not only expected to lead departments, faculties and schools, but also to set the intellectual tone of the university and serve as role models for academic excellence and integrity.

To rise to this level is to belong to a rarefied circle of scholars whose labour sustains the very idea of a university. For such an individual, one of only a few thousand in the whole of Nigeria, to be found in the market selling vegetables is nothing short of a national embarrassment. Of this already small number, many are close to retirement, others are already retiring, and few are dying quietly and prematurely, having laboured for years without adequate compensation, with their health as the price of neglect.

The image of a Nigerian professor selling vegetables is not a symbol of entrepreneurship; it is a stark emblem of a system that has failed to awaken to the true value of knowledge. It illustrates what happens when a nation treats its intellectuals as expendable. It lays bare the bitter truth that Nigerian professors are among the least paid in the world. In some African countries, full professors earn salaries that are incomparably higher than those of their Nigerian counterparts. How, then, can Nigeria expect its academics to compete globally when their economic conditions have reduced them to mere survival hustlers?

The danger before us is not merely economic; it is also intellectual and moral. A professor of Agriculture who is preoccupied with how to feed his family cannot be expected to produce groundbreaking research. Instead of spending long hours in the laboratory developing improved crop varieties, he finds himself in the field cultivating vegetables for sale. If such a professor were adequately compensated, his “community service” should not be at the market stall but in leading innovation for food security, researching drought-resistant crops, strengthening plant genetics, or mentoring farmers on sustainable agricultural practices. That is the kind of knowledge transfer a professor owes society, not hustling to survive in the marketplace. Instead of mentoring young scholars with patience and vision, his mind is weighed down by the daily anxieties of survival.

READ ALSO: No injunction granted against David Mark, Aregbesola — ADC

Gradually, this displacement erodes the very soul of academia. Lecturers are pushed into moonlighting, chasing consultancies, and juggling side hustles, while the quality of teaching and research inevitably declines. When a professor is forced to struggle just to provide decent meals for his family, pay his children’s school fees, and maintain a modest standard of living, distraction is inevitable. That distraction deepens when his inadequate salary is not even paid at the end of the month, but trickles in only by the first or second week of the next.

The Academic Staff Union of Universities (ASUU) must be commended. For years, ASUU has insisted, often at great personal sacrifice of its members on the need for better welfare and a stronger university system. The union has consistently warned that neglecting lecturers’ welfare is a direct assault on the ivory tower itself. Their struggles, frequently misunderstood, are in fact a demand for the survival of quality higher education in Nigeria. By fighting for fair compensation, adequate funding, and improved conditions of service, ASUU has kept the conversation alive and has prevented the total collapse of the Nigerian university system.

A globally competitive pay package is not a luxury; it is an absolute necessity. It is the only way Nigeria can retain its brightest academics, attract its best graduates into the ivory tower, and give universities a good chance in global rankings. Paying lecturers well means they can devote their full intellectual energy to teaching, research, and innovation. It means a lecturer can concentrate on developing cutting-edge research rather than being helplessly found wondering around for economic survival. Government must realize that investing in the pay of lecturers is an investment in the nation’s future. No nation can rise above the quality of its teachers, and no teacher can give their best when treated as a beggar. If Nigeria wants graduates who can continually stand shoulder to shoulder with their peers the world over, then Nigerian lecturers must be paid on a scale that allows them to contribute globally.

This is where the Minister of Education must rise to the occasion. Mr Minister, history has placed upon you the responsibility of rescuing Nigerian universities from this perilous cycle. You are well travelled and have experienced the global best practices that sustain universities in advanced nations. As a professional and an Assistant Professor yourself, you know firsthand the dignity and reward that accompany academia in other climes. Nigeria deserves no less. Fight this just cause. Lead the campaign for a better pay package. Let it be said that under your stewardship, Nigeria restored the dignity of its professors and secured a future for its universities. Engrave your name in history as the Minister who turned the tide. The Nigerian university system cannot wait. The nation’s future cannot wait.

The story of the professor of plant physiology should not be dismissed as an oddity. It is a warning sign, a reminder that if we continue to treat professors as market hustlers, Nigeria will never become a knowledge economy. Paying them decently is not doing them a favour; it is saving the nation from intellectual decay.

Prof. Adebola A. ADERIBIGBE, Federal University Oye-Ekiti, Ekiti State, Nigeria

-

Politics2 hours ago

Politics2 hours agoSowore sues Nigerian govt, Meta, X for rights violations

-

News1 hour ago

News1 hour agoTinubu returns to Abuja after 12-day trip abroad

-

Politics1 hour ago

Politics1 hour agoLagos APC hits back at Peter Obi, says Tinubu’s borrowing strategic, not reckless

-

Politics58 minutes ago

Politics58 minutes agoPresidency counters Atiku, cites rising reserves, falling inflation as proof of progress

-

News53 minutes ago

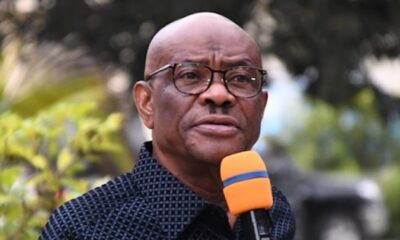

News53 minutes agoWike defends Rivers LG elections, accuses Atiku, Obi of misrepresenting the law

-

News49 minutes ago

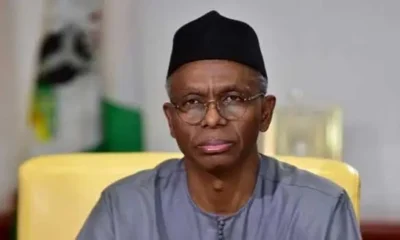

News49 minutes ago’Submit yourself for scrutiny over allegations,’ Northern youths challenge El-Rufai

-

News44 minutes ago

News44 minutes ago‘Don’t provoke bandits after peace deals in Katsina’, Sheikh Gumi warns military

-

Sports40 minutes ago

Sports40 minutes agoHaaland bags brace as City win Manchester derby, Liverpool beat Burnley