Business

Nigeria’s food import waiver cut prices and wiped N5trn off farmers’ incomes in 2025

A 150-day duty-free import window helped tame food inflation but left local farmers with excess produce, heavy losses and rising uncertainty over future food supply.

In July 2024, the Nigerian government announced a 150-day duty-free import window for key food staples like maize, husked brown rice, wheat, and cowpeas—to combat high food inflation.

The idea was simple: increase food circulation, pull food inflation down, and deliver significant relief to Nigerians, who at the time were under the weight of surging food prices.

But BusinessDay findings show that the policy, while easing consumer prices, triggered one of the steepest income shocks Nigeria’s agric sector has faced in recent years.

The waiver was supposed to run from July 15 to December 31, 2024, but did not kick off until sometime in January 2025. It was a five-month window in which selected food imports entered Nigeria at zero or significantly reduced duty rates, depending on the commodity.

The policy was announced just a month after the country’s food inflation hit a record high of over 40 percent in June 2024.

The problem, however, was that local farmers’ production entered import-saturated markets that did not need more food, making them unable to make profit.

This left farmers with excess commodities, which led to financial loss of about N5 trillion between 2024 and 2025, according to data from the Foundation for Peace Professionals (PeacePro).

Nigeria remains dependent on imports to fix its food supply gap. The country has a food sufficiency challenge that has led the World Bank to project that about 34.7 million people would experience food insecurity this year.

Consumers benefits

The policy delivered some measurable benefits for consumers. Food inflation dropped from 26.08 percent in January 2025 to 10.87 percent in December 2025, driven by a crash in food prices.

A 50kg bag of foreign rice fell to an average of N57,000 from N88,000 in 2024. While prices of local rice also fell to an average of N65,000 from a high of about N105,000 in 2024.

Similarly, a metric ton of maize dropped 29 percent from N600,000 in 2024 to N426,000 at the farm gates.

Cassava prices tumbled by more than 50 percent in one year. High import of ethanol, a by-product of cassava, pushed cassava farmers out of markets as processors found that imported ethanol was cheaper than locally produced.

Toyosi Olatayo, founder of Palmira Farm Trade, an agro firm involved in cassava business, told BusinessDay that “it became cheaper for processors to import ethanol and starch than buy from local farmers because farmers’ price rate was so high”.

Farmers squeezed, rising imports

Behind the lower food prices was a growing crisis among farmers across the country, many of whom were unable to sell their produce or recover production costs.

“Farmers ran into huge financial losses. It was a national calamity,” Binta Abdulkarim, a large-scale farmer in Kano State, told BusinessDay.

The policy also spiked Nigeria’s food import bill from N2.70 trillion from January to September of 2024 to N3.32 trillion in the same period of 2025, an increase of 23 percent.

The loss was so dire that farmers are beginning to lose interest in farming.

“We are trying to beg our farmers not to be discouraged but to go back to farming. A lot of them are saying they will not farm this year,” said Muhammed Magaji, president of the All Farmers Association of Nigeria (AFAN).

Loopholes of the policy

Although the intentions of the policy were for the good of the Nigerian people, experts say it was done without proper planning for local production.

“The government should have had some kind of arrangement with farmers where they offtake the excess that was produced and store it,” said Shehu Bello, a large-scale farmer in Abuja.

According to agric experts, the policy did not create some form of shock absorber for farmers who invested heavily in production despite high input costs.

“There should have been a regulation that allowed farmers to compete fairly, but we didn’t have that. We could not compete,” Bello said.

Tunde Banjoko, Agric president of the Lagos Chamber of Commerce and Industry (LCCI), in an interview with BusinessDay, said artificially crashing prices is not sustainable and “it is the reason a lot of farmers are quitting”.

“The federal government should have supported farmers by subsidising input costs to boost local production rather than focusing on importation,” he said.

Storage gaps

Nigeria’s weak storage infrastructure magnified the damage. With no buyers and limited warehousing, farmers were forced to sell at a loss or watch produce spoil.

Agric experts argue that Nigeria’s poor storage infrastructure could not accommodate farmers’ excess, especially when they couldn’t find buyers.

“We keep stressing on boosting food production, but we don’t even have adequate storage facilities to store what we produce,” Abiodun Olorundero, an agric expert, told BusinessDay.

Lessons from the Philippines

Nigeria’s experience contrasts sharply with how similar policies are managed elsewhere.

The Philippines has long used protectionist policies for certain agricultural commodities to ease food prices, just as Nigeria did. However, the difference between the two countries is in approach.

When the Asian nation had a duty waiver policy on sugar importation, it was controlled by the Sugar Regulatory Administration (SRA) to prevent oversupply that could hurt local sugarcane farmers.

But for Nigeria, there was no regulation to control importation.

Way out

Experts warn that without deliberate inclusion of farmers in future policy design, similar interventions risk triggering another round of losses. (BusinessDay)

-

Politics23 hours ago

Politics23 hours agoAPC Congress: Ogun, Lagos Retain Chairmen, Ondo, Oyo Elect Babatunde, Adeyemo

-

News23 hours ago

News23 hours agoDSS Arrests Police, Immigration Officials ‘Implicated’ In El-Rufai’s Return To Nigeria

-

Sports23 hours ago

Sports23 hours agoRonaldo ‘Flees’ Saudi Arabia Amid Bombardment From Iran

-

News23 hours ago

News23 hours agoRivers Assembly unveils Fubara’s commissioner nominees

-

News22 hours ago

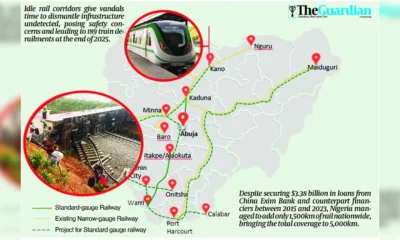

News22 hours agoFaulty design, vandalism, neglect endanger $3.4b rail overhaul

-

Celebrity Gist22 hours ago

Celebrity Gist22 hours agoDiddy set for earlier prison release

-

Business23 hours ago

Business23 hours agoBusinesses Bleed As Blackout Worsens

-

News22 hours ago

News22 hours agoFG suspends pilgrimages to Israel over Middle East security situation